To elucidate whether that's a reasonable and, more importantly, sufficient (meaning: "Is the increased energy expenditure high enough to explain the fat loss, even if the steady state exercise consumes more energy and fat on total?") explanation for the previously mentioned advantages, researchers from the Healthy Lifestyles Research Center at the Arizona State University conducted a study to compare the EPOC response to the three most common forms of aerobic training: high intensity interval exercise (HIE), sprint interval exercise (SIE), and steady state exercise (SSE).

You can learn more about HIIT at the SuppVersity

- HIE (four 4-min intervals at 95% HRpeak, separated by three min of active recovery); and

- SIE (six 30-s Wingate sprints, separated by four min of active recovery); and

- SSE (30 min at 80% of peak heart rate (HRpeak)).

|

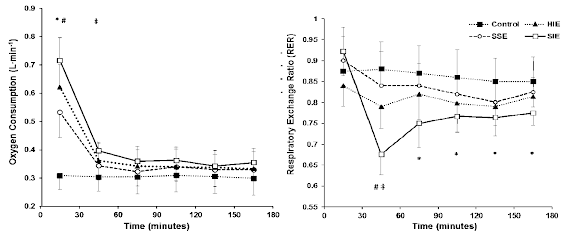

| Figure 1: Oxygen consumption and respiratory exchange ratio (higher numbers = higher carbohydrate to fat oxidation ratio) during the first three hours after exercise (Tucker. 2016). |

There's room for "cardio": Even though it is not popular, these days, it would be wrong to assume that classic steady state training is always the inferior choice. For someone who's killing it in the gym regularly, the additional HIIT training may in fact be too much of a sympathetic stimulus. The "boring" classic "cardio" training, on the other hand, is predominantly parasympathetic, which is why walking on an incline treadmill may eventually be a better complement to your 4-5 resistance training sessions per week than HIIT cycling or sprinting.

It is thus not really surprising that both, the complete 3-h EPOC and the total net EE after exercise were not extremely different and that that 3-h EPOC and total net EE after exercise were higher (p=0.01) for SIE (22.0 ± 9.3 L; 110 ± 47 kcal) compared to SSE (12.8 ± 8.5 L; 64 ± 43 kcal).Bottom line: As Tucker et al. rightly point out, simple math shows that the increased energy expenditure and O2 consumption during the steady state trial more than compensates the significant, but small increase in energy expenditure and fat oxidation after the workout.

It is important to know that this does not negate the results of previous studies that found beneficial effects of HIIT on fat loss. What the study does do, however, is to refute the hypothesis that these benefits were a result of an increase in EPOC and thus overall larger total energy expenditure. This, on the other hand, doesn't mean that any effects after the EPOC window of 3h investigated in the study could be responsible for said benefits. As Tucker et al. highlight, "another previously confirmed benefit of intense exercise is that it can increase the resting energy expenditure (REE) [... 17-24 h after exercise ...] in part due to an increase in sympathetic tone " (Tucker. 2016).

In conjunction with increases in the ease of locomotion (16, 17) and increase nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) (14), these effects could well explain the benefits of HIIT. Studies to confirm that are yet not just lacking, as Tucker et al. highlight, the whole-room calorimeter study of Sevits et al. (32) even suggests that SIE does not elevate REE at 24 h postexercise (see Figure 3). More studies to get to the bottom of the fat loss benefits of HIIT protocols appear warranted | Comment.

References: |

| Figure 3: Minute-by-minute energy expenditure during a sedentary day and a day beginning with a single bout of sprint interval training (SIT). Data are mean values (Sevits. 2016). |

In conjunction with increases in the ease of locomotion (16, 17) and increase nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) (14), these effects could well explain the benefits of HIIT. Studies to confirm that are yet not just lacking, as Tucker et al. highlight, the whole-room calorimeter study of Sevits et al. (32) even suggests that SIE does not elevate REE at 24 h postexercise (see Figure 3). More studies to get to the bottom of the fat loss benefits of HIIT protocols appear warranted | Comment.

- Sevits, Kyle J., et al. "Total daily energy expenditure is increased following a single bout of sprint interval training." Physiological reports 1.5 (2013): e00131.

- Tucker, Wesley J., Siddhartha S. Angadi, and Glenn A. Gaesser. "Excess postexercise oxygen consumption after high-intensity and sprint interval exercise, and continuous steady-state exercise." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research (2016).