|

| With high protein diets often being falsely equated with misguided varieties of keto diets where you eat nothing but sausages and bacon, the public jumps at 'news' like "A new study suggests there's a downside to all that protein" (time.com) and ignores that high protein dieters like you and me limit the amounts of these foods and eat way more veggies and fruits than Mr. Average is often forgotten in the debate. |

That's a daring hypothesis, I know, but my own bias towards higher protein diets is not the only reason I do not subscribe to the what Bettina Mittendorfer, co-author of the study and a professor of medicine, argues in the previously cited article on time.com: "There’s no reason to [follow a high(er) protein diet], and potentially there is harm or lack of a benefit" (quote from the time.com article).

High-protein diets are much safer than some 'experts' say, but there are things to consider...

- a hypocaloric diet (-30% energy intake) containing 0.8 g protein/kg/day (NP) to a

- a hypocaloric diet (-30% energy intake) containing 1.2 g protein/kg/day (HP)

|

| Figure 1: Flow of study participants (from supplemental material for Smith. 2016) |

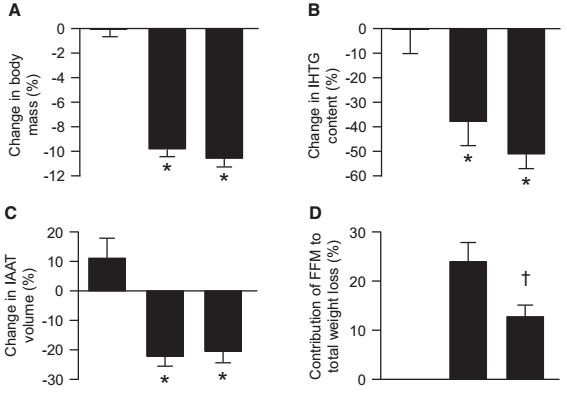

Good news #1: Eating 150% of the RDA for protein while dieting reduces postmenopausal women's diet-induced lean mass losses significantly.

Unfortunately, the often-cited abstract to the study (and the press release that's at the heart of the mass media coverage I hinted at in the introduction) creates the impression that this was the only positive result, the scientists observed in a study the most important finding of which was that the "HP [high protein] intake also prevented the WL[weight loss]-induced improvements in muscle insulin signaling and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake".

- no difference in basal and insulin and glucose levels, or the insulin and glucose levels in response to a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp test you would expect to see both if the subjects' glucose management worsened significantly due to the increased protein intake,

- no difference in free fatty acid levels at rest and during the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp as you would expect them if the high protein intake had had a negative effect on the subjects' glucose and subsequently fatty acid metabolism,

- no difference in the reduction of the amount intra-hepatic triglyceride (liver fat), which has been associated with significant decreases in full-body insulin resistance,

- no difference in the effect of the global inflammation markers hs-CRP and IL-6, which could explain the allegedly worsened glucose metabolism in the HP group,

- no differences in the loss of intra-abdominal fat, which is among the most important determinants of whole body inflammation and thus - again - one's insulin sensitivity

- no difference in the small and mostly non-significant effect of the treatment on the expression of genes involved in lipogenesis, and fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial function in muscle that could potentially explain the emphasized "downside to all that protein" (time.com)

- no difference in the change of AMPK, the master regulator of cellular energy homeostasis

- no difference in serum BCAA levels, of which previous studies have shown that their accumulation in the blood is at least correlated with the development of obesity and a worsening of glucose management (She. 2007)

Good news #2: Eating 50% more protein does not significantly affect the value and/or change of eight other biological markers you'd expect to differ if eating 1.2g/kg protein while you are dieting would ameliorate, if not reverse the benefits of body weight and fat loss.

Now, none of these "good news" invalidates the scientists' analysis of glucose dynamics during the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp procedure (HECP), of which the scientists say (not without reason, by the way) that they were indicative of the fact that a "HP intake also prevented the WL-induced improvements in muscle insulin signaling and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake" (Smith. 2016). What these "good news" do, however, is to warrant the question how practically significant this observation actually is - after all, you would expect, and I know that I am repeating myself here, insulin, glucose, inflammation, visceral fat and the other parameters listed above and/or the way they changed over the course of the study to differ between groups, as well.

Food for thought: What does the HECP actually measure and how representative is that of what you would see under 'real-world conditions'?

A lack of changes outside of the HECP makes the quest for potential mechanisms even more important. The scientists, however, cannot even explain the "adverse effect of HP intake on insulin

action", in general. They call it "unclear" (Smith. 2016) and argue, just like me, that this is particularly true in view of the "absence of any major differences in body weight, body composition, plasma FFA availability, and inflammatory markers" (Smith. 2016). Based on the increase of the glutathione recycling gene GSTA4 and expression of PRDX3 a muscle-specific gene that's increased when animal muscle is exposed to oxidative stress, Smith et al. argue that eventually their results

"[...] suggest that the adverse effect of HP intake on insulin action during weight loss therapy may have been mediated through its effects on oxidative stress because it prevented the WL-induced decrease, and even increased, metabolic pathways involved in oxidative stress response in muscle" (Smith. 2016).This is yet only one possible explanation. Another hypothesis that would explain the differences in the extreme situation of the HECP, i.e. the continuous infusion of glucose under hyperinsulinemic conditions as you would like and in 99% of the cases can avoid them in reality, can be derived based on data from a Y2K study by Linn, et al. In this study, the authors investigated the long-term effects of high protein diets (1.8g/kg vs. 0.7g/kg) on glucose metabolism without weight loss and found one effect of high protein diets, Smith et al. ignore completely:

Remember: Irrespective of the argument that the result may be a methodological artifice and potentially of limited practical significance, a more important and non-hypothetical argument against panicking is that we are dealing with a single study in a very specific part of the population. It's thus not the time for over-generalizations and hectic responses, yet.

In the HECP, on the other hand, the insulin levels of both groups will be the same, namely maxed out. The previously described compensation that occurs in the real world and in response to real food and the other gold-standard of measuring an individual's glucose metabolism, the oral glucose tolerance test, is thus physiologically impossible in the artificial hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp procedure - and the 2003 study by Farnsworth would confirm that: In the "real world", i.e. under dynamic insulin conditions as you would see them with both, the oral glucose tolerance test, Farnsworth et al. conducted and the ingestion of a real meal, practically relevant disadvantages of the chronic consumption of a high protein diet don't exist.

|

| I openly admit that I am, based on the plethora of scientific evidence in its favor, biased towards high(er) protein diets. What I am not, though, is blind to potential downsides of high protein intakes. You can read about one I've discussed only recently in "Protein Oxidation 101: 8 Simple Rules to Minimize PROTOX and Maximize the Proven Benefits of High(er) Protein Diets" I don't ignore potential downsides of this way of eating and for me, the Smith study alone does not provide convincing evidence of another downside of high(er) protein intakes. |

What all studies, including the one at hand, report, though, is that the increase in protein intake will have beneficial effects on the subjects' body composition by preserving lean, and in many cases promoting fat mass loss without messing with the classic measures of glucose metabolism: insulin, fasting glucose, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, or the previously mentioned oral glucose tolerance test (Brinkworth. 2004 a,b; Sargrad. 2006; Claessens. 2009; Hession. 2009) | Comment!

- Brinkworth, G. D., et al. "Long-term effects of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on weight control and cardiovascular risk markers in obese hyperinsulinemic subjects." International journal of obesity 28.5 (2004a): 661-670.

- Brinkworth, G. D., et al. "Long-term effects of advice to consume a high-protein, low-fat diet, rather than a conventional weight-loss diet, in obese adults with type 2 diabetes: one-year follow-up of a randomised trial." Diabetologia 47.10 (2004b): 1677-1686.

- Claessens, M., et al. "The effect of a low-fat, high-protein or high-carbohydrate ad libitum diet on weight loss maintenance and metabolic risk factors." International journal of obesity 33.3 (2009): 296-304.

- Farnsworth, Emma, et al. "Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women." The American journal of clinical nutrition 78.1 (2003): 31-39.

- Han, Seung Seok, et al. "Lean mass index: a better predictor of mortality than body mass index in elderly Asians." Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 58.2 (2010): 312-317.

- Hession, M., et al. "Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low‐carbohydrate vs. low‐fat/low‐calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities." Obesity reviews 10.1 (2009): 36-50.

- Leidy, Heather J., et al. "Higher protein intake preserves lean mass and satiety with weight loss in pre‐obese and obese women." Obesity 15.2 (2007): 421-429.

- Linn, T., et al. "Effect of long-term dietary protein intake on glucose metabolism in humans." Diabetologia 43.10 (2000): 1257-1265.

- Mettler, Samuel, Nigel Mitchell, and Kevin D. Tipton. "Increased protein intake reduces lean body mass loss during weight loss in athletes." Med Sci Sports Exerc 42.2 (2010): 326-37.

- Piatti, P. M., et al. "Hypocaloric high-protein diet improves glucose oxidation and spares lean body mass: comparison to hypocaloric high-carbohydrate diet." Metabolism 43.12 (1994): 1481-1487.

- Sargrad, Karin R., et al. "Effect of high protein vs high carbohydrate intake on insulin sensitivity, body weight, hemoglobin A1c, and blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus." Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105.4 (2005): 573-580.

- She, Pengxiang, et al. "Obesity-related elevations in plasma leucine are associated with alterations in enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid metabolism." American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 293.6 (2007): E1552-E1563.

- Smith, Gordon I., et al. "High-protein intake during weight loss therapy eliminates the weight-loss-induced improvement in insulin action in obese postmenopausal women." Cell Reports 17.3 (2016): 849-861.