|

| Even on the five fasting days per month your plate doesn't have to be completely empty. Real foods, however, weren't served in this trial. |

Now, as effective and healthy as it may be, fasting is not exactly what the average pre-diabetic (of whom the study at hand shows that he would benefit most) wants to do and/or what he or she can adhere to in the long run.

Learn more about fasting at the SuppVersity

- day 1: ~4600 kJ = 1100kcal | 11% protein, 46% fat, and 43% carbohydrate

- day 2-5: ~3000 kJ = 717kcal | 9% protein, 44% fat, and 47% carbohydrate

|

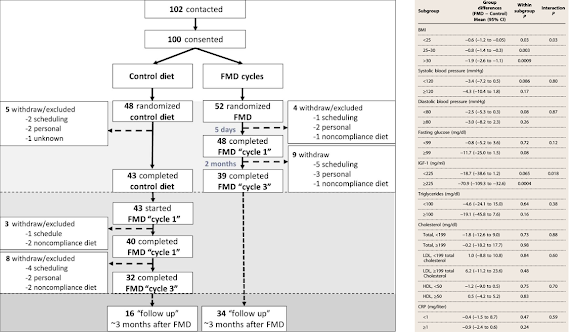

| Figure 1: Overview of the study design (left) and post hoc comparisons for changes in risk factors for age-related diseases and conditions by baseline subgroups (right | Wei 2017). |

|

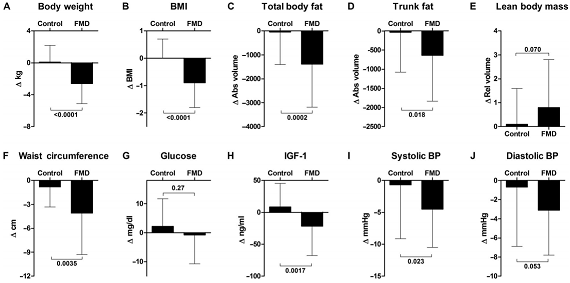

| Figure 2: Overview of changes in several markers of metabolic and overall health (Wei 2017). |

The parameters improved, but you may still not live longer or stay healthier! It's not the lack of improvements in plasma lipids an it's neither the relatively small effect size of many changes. It is the mere fact that the glucose, insulin, IGF1 and triglyceride levels of the average Westerner will still skyrocket acutely on the 25 days of the months on which they don't fast. And that's really bad news, because many of the unassessed markers like the postprandial glucose and lipid levels are highly significant predictors of heart disease (Lefebvre 1998; Hanefeld 1999; O’Keefe 2007) or cancer (Michaud 2002; Prescott 2014; Larsson 2016) - to reduce the level of fasted / non-postprandi-ally measured markers of disease risk is thus clearly not enough to predict the true reduction of disease risk.

Bottom line: Overall, it is thus prudent to say that the three FMD cycles every subject underwent triggered significant reductions in body weight, trunk, and total body fat; lowered blood pressure and decreased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) without serious side effects.What looks like an easy way out does yet also have it shortcomings: (a) the subjects' blood lipids did not improve (neither total, nor LDL, or HDL cholesterol and their ratios); (b) the treatment may have been free of health-relevant side-effects, side-effects that will have many people fall off the wagon, however, existed, nevertheless (e.g. fatigue, weakness or headache see additional figure); (c) with no effect on peak values of glucose, insulin, IGF-1 etc. on the non-fasting days, it's far from being obvious that the treatment will have any of the hoped for long-term effect.

Especially (c) is something you should remember: before the scientists produce the long-term evidence that confirms that 5 days every month are enough to let you live longer, reduce your cancer, CVD and diabetes risk, I still recommend to change your lifestyle on 365 days of the year - that's the tried and proven method to live long(er) and healthy(-ier) | Comment!

- Hanefeld, M., et al. "Postprandial plasma glucose is an independent risk factor for increased carotid intima-media thickness in non-diabetic individuals." Atherosclerosis 144.1 (1999): 229-235.

- Larsson, Susanna C., Edward L. Giovannucci, and Alicja Wolk. "Prospective Study of Glycemic Load, Glycemic Index, and Carbohydrate Intake in Relation to Risk of Biliary Tract Cancer." The American journal of gastroenterology (2016).

- Lefebvre, P. J., and A. J. Scheen. "The postprandial state and risk of cardiovascular disease." Diabetic Medicine 15.S4 (1998).

- Michaud, Dominique S., et al. "Dietary sugar, glycemic load, and pancreatic cancer risk in a prospective study." Journal of the National Cancer Institute 94.17 (2002): 1293-1300.

- O’Keefe, James H., and David SH Bell. "Postprandial hyperglycemia/hyperlipidemia (postprandial dysmetabolism) is a cardiovascular risk factor." The American journal of cardiology 100.5 (2007): 899-904.

- Prescott, Jennifer, et al. "Dietary insulin index and insulin load in relation to endometrial cancer risk in the Nurses' Health Study." Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers (2014): cebp-0157.