You can learn more about sweeteners at the SuppVersity

How can you be so sure that there's no causal relationship between mustaches and sales?

In all honesty, you can't be 100% certain. Why's that? Well, in contrast to the issue of non-nutritive sweeteners (NNSs), obesity and metabolic disease, there are no RCTs available that refute the claim that long mustaches are driving the increase in sales that's illustrated in Figure 1. It is thus haphazard to abuse the meta-analysis by Azad et al. to 'prove' that "routine intake of nonnutritive sweeteners may be associated with increased BMI and cardiometabolic risk" (Azad 2017).

I don't have to remind you of the limitations of observational studies, do I? In 2014 Maki et al. wrote in their paper "Limitations of observational evidence: implications for evidence-based dietary recommendations" that imprecise exposure quantification, collinearity among dietary exposures, displacement/substitution effects, healthy/unhealthy consumer bias, residual confounding, and effect modification are only some of the various limitations of observational evidence and "advocate for greater caution in the communication of dietary recommendations for which RCT evidence of clinical event reduction after dietary intervention is not available".

Now, guess what: for artificial sweeteners, the (albeit insufficient) RCT evidence points to beneficial effects. Nevertheless, the accepted public opinion appears to be that artificial sweeteners make you fat and sick. A conclusion that is clearly unwarranted based on the available experimental evidence - irrespective of how biased you believe it was.

It is true that Azad et al. conclude, based on the results of a thorough search of MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Library (inception to January 2016) for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated interventions for nonnutritive sweeteners and prospective cohort studies that reported on consumption of non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS) among adults and adolescents, that there's a link between the primary outcome of the study, i.e. body mass index (BMI), as well as secondary outcomes including weight, obesity and other cardiometabolic end points and the subjects' NNS consumption.Now, guess what: for artificial sweeteners, the (albeit insufficient) RCT evidence points to beneficial effects. Nevertheless, the accepted public opinion appears to be that artificial sweeteners make you fat and sick. A conclusion that is clearly unwarranted based on the available experimental evidence - irrespective of how biased you believe it was.

|

| Diet Sodas Contain More Than 5 Non-Sweetening Ingredients that May Mess W/ Your Glucose Management | learn more |

The two 6-month interventions, on the other hand, did not find a significant effect on waist circumference and another 6-month trial failed to identify effects on the subjects' percentage of body fat.

Waist reductions only in industry-funded studies? Yes, but...

While it must not be forgotten, that there was also (c) an effect of the previously discussed industry funding on the significance of the results, with a statistically significant reductions in waist circumference being observed only in the industry-funded studies, you should be aware of the fact that the corresponding non-funded study by Madjid et al. (2015) did not reflect regular sweetener use as it can be observed in the general population. Instead of making non-nutritively sweetened beverages one of the main sources of hydration in the subjects, the scientists had their obese participants consume only a single serving of a wantonly undefined "diet beverage" with only one meal (lunch) on only 5 days of the week. For the rest of the day, both groups were asked not to drink DBs or water during the meal and also not add low-calorie sweeteners such as aspartame or sucralose to beverages such as tea or coffee. You don't really think that's an appropriate study design, do you?

|

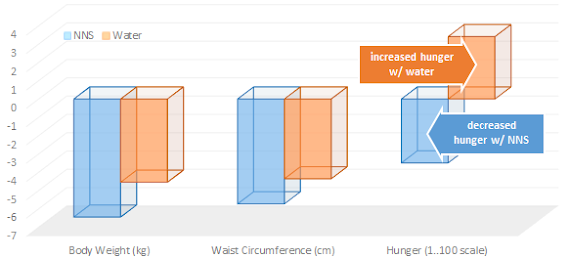

| Figure 2: Changes in body weight, waist circumference & hunger in the course of the 12-week study (Peters. 2014) |

|

| Drinking only 2/3rds of this can may change your microbiome. Whether this difference is health relevant is yet as questionable as whether the alleged effects are positive or negative | more. |

And that's significantly different from the mainstream interpretation of the summary ScienceDaily and Co will give you: "Artificial sweeteners may be associated with long-term weight gain and increased risk of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease, according to a new study" (ScienceDaily intro from 17 July 2017).

Ah, and no... there's no evidence that artificial sweeteners change the microbiome in a way that promotes any of the aforementioned health problems. I've discussed the difference between "observing changes" and "observing changes that cause disease" in my 2015 article"Anti-Microbial Effects of Artificial Sweeteners in Humans - 2/3rds of a Can of Diet Coke May Have a Sign. Effect on the Gut Microbiome, but the Relevance is Questionable". If you haven't read it yet, I suggest you make good for that. Plus: If you want to worry about artificial sweeteners and obesity, worry about the way(s) it may be promoting (or at least maintaining) your sweet tooth | Comment on Facebook!

- Azad, et al. "Nonnutritive sweeteners and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies." Canadian Medical Association Journal 189.28 (2017): E929 DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.161390

- Blackburn, George L., et al. "The effect of aspartame as part of a multidisciplinary weight-control program on short-and long-term control of body weight." The American journal of clinical nutrition 65.2 (1997): 409-418.

- Ferri, Letícia AF, et al. "Investigation of the antihypertensive effect of oral crude stevioside in patients with mild essential hypertension." Phytotherapy Research 20.9 (2006): 732-736.

- Hsieh, Ming-Hsiung, et al. "Efficacy and tolerability of oral stevioside in patients with mild essential hypertension: a two-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study." Clinical therapeutics 25.11 (2003): 2797-2808.

- Madjd, Ameneh, et al. "Effects on weight loss in adults of replacing diet beverages with water during a hypoenergetic diet: a randomized, 24-wk clinical trial." The American journal of clinical nutrition 102.6 (2015): 1305-1312.

- Peters, John C., et al. "The effects of water and non‐nutritive sweetened beverages on weight loss during a 12‐week weight loss treatment program." Obesity 22.6 (2014): 1415-1421.

- ScienceDaily. Canadian Medical Association Journal. "Artificial sweeteners linked to risk of weight gain, heart disease and other health issues." ScienceDaily, 17 July 2017. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/07/170717091043.htm>.

- Tate, Deborah F., et al. "Replacing caloric beverages with water or diet beverages for weight loss in adults: main results of the Choose Healthy Options Consciously Everyday (CHOICE) randomized clinical trial." The American journal of clinical nutrition 95.3 (2012): 555-563.