|

| About time for another installment of the SuppVersity Short News. Isn't it? Today: Stretching + Glycemia, Curcumin + Weight(-Re)Gain, ARA + Inflammation |

Read about exercise- and nutrition-related studies in the SuppVersity Short News

- Curcumin's anti-inflammatory cortisol reducing effects may help you stay lean (Teich 2017) -- To get shredded is easy... compared to staying shredded, that is. Whence you stop training and start cheating on your diet, the weight regain, adipose tissue growth, and insulin resistance can occur within days after the cessation of regular dieting and exercise.

As Trevor Teich and colleagues point out in their latest paper, "[t]his phenomenon has been attributed, in part, to the actions of stress hormones as well as local and systemic inflammation" (Teich 2017).

In the corresponding experiment, the scientists investigated the effect of curcumin, a naturally occurring polyphenol known for its anti-inflammatory properties and inhibitory action on 11β-HSD1 activity (that's the enzyme that converts inactive cortisone to cortisol), on preserving metabolic health and limiting adipose tissue growth following the cessation of daily exercise and caloric restriction (CR).![]()

Figure 1: Graphical overview of the effects on body composition and glucose management (Teich 2017).

And yes, we're talking about a rodent study: Sprague-Dawley rats (6–7 wk old) underwent a “training” protocol of 24-h voluntary running wheel access and CR (15–20 g/day; ~50–65% of ad libitum intake) for 3 wk (“All Trained”) or were sedentary and fed ad libitum (“Sed”). After 3 wk, All Trained were randomly divided into one group which was terminated immediately (“Trained”), and two detrained groups which had their wheels locked and were reintroduced to ad libitum feeding for 1 wk. The wheel locked groups received either a daily gavage of a placebo (“Detrained + Placebo”) or curcumin (200 mg/kg) (“Detrained + Curcumin”). And the results were interesting, to say the least:- Cessation of daily CR and exercise caused an increase in body mass, as well as a 9- to 14-fold increase in epididymal, perirenal, and inguinal adipose tissue mass, all of which were attenuated by curcumin (P < 0.05).

- Insulin area under the curve (AUC) during an oral glucose tolerance test, HOMA-IR, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were elevated 6-, 9-, and 2-fold, respectively, in the Detrained + Placebo group vs. the Trained group (all P < 0.05).

- Curcumin reduced the increae in insulin AUC, HOMA-IR, and CRP vs. the placebo group (all P < 0.05).

- Stretching for blood sugar control (Gurudut 2017) -- It's not necessarily news, as previous studies have already reported beneficial effects of stretching on glucose management, but it's certainly not common knowledge that stretching can have similar (post-meal) glucose reducing effects as resistance training.

In a recent study, scientists from the KLEU Institute of Physiotherapy in India identified and compared the immediate effect of passive static stretching (PSS) on blood glucose level in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The study included 51 participants between the age of 40-65 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus, to study the immediate effect of 60-min PSS (n=25) and 60-min RE (n=26). The outcome was compared to a standardized resistance training routine. Blood sugar was assessed at 3 points of time that included fasting blood sugar level, 2 hr after the meal and immediately after the exercise regimen. Results of this study showed a significant reduction in blood glucose level in subjects according to glucometer with PSS (P=0.000) and RE (P=0.00).

In spite of the greater significance (lower p-value) of the stretching regimen and the greater decrease in glycemia in the resistance training group, it is important to note that "both groups demonstrated equal effects in terms of lowering blood sugar level immediately after the exercise" (Gurudut 2017). Accordingly, the two should be interchangeable in type 2 diabetics who want to control their post-prandial blood glucose spike.![]()

Figure 2: Within the statistical margin of error stretching and resistance training are equally effective in reducing the post-prandial glucose surge in type II diabetics (Gurudut 2017).

In view of the fact that similar results have been reported before by Nelson et al. (2011 | in 22 adults (17 males) either at increased risk of Type 2 diabetes or with Type 2 diabetes) and Park (2015 | 15 patients (8 males and 7 females) with type 2 diabetes), it is getting increasingly hard to ignore stretching as a potentially health-benefitting intervention in people with impaired blood sugar control.

- Arachidonic acid for strength trainees revisited: Improved myogenic response, no issues w/ increased inflammation (Markworth 2017) -- If you've been around for some years, you will remember the "ARA-craze" surrounding the marketing campaign of a supplement called "X-factor". According to its producers, this supplement which contained what some people deem to be the evil twin brother of DHA + EPA (fish oil) would significantly increase your gains by modulating the inflammatory response to exercise...

... now, as a regular at the SuppVersity the notion of "modulating the inflammatory response" should bring up two questions: (1) If it's an anti-inflammatory response will the hormetic effects of exercise be blunted and your gains be reduced? (2) If it's a pro-inflammatory response (which is what you'd expect with arachidonic acid), could it be downright unhealthy?![]()

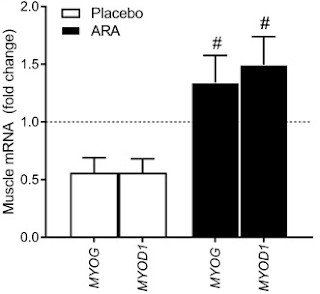

Figure 3: The increase in myogenic gene expression is neither small nor non-significant (Markworth 2017), but its real-world effects in terms of gains have been shown to be disappointing (Roberts 2007).

Even though ARA is generally associated with increased inflammation, studies have actually observed (1), i.e. a reduction in the pro-inflammatory response to exercise (Roberts 2007).

It is thus not exactly surprising that it can increase the expression of myogenic regulatory factors, MyoD, and myogenin, without triggering collateral damage in form of impairments of the immune system or abnormal increases in inflammatory cytokines... at least not within a time-frame of four weeks, over the course of which N=9 resistance trained men (≥1 year) received dietary supplementation with 1.5 g/day ARA, in the study at hand - a study that did not, as Roberts et al. did it in 2007 assess the longterm effects on gains (note: Roberts et al. found no "greater gains in strength, muscle mass, or influence markers of muscle hypertrophy" (Roberts 2007).![]()

Table 1: Few of us run the risk of arachidonic acid deficiency. Here is where we get most of our daily/cumulative intakes: chicken, eggs, beef... ah and pasta and grains (National Cancer Institute).

Thus, despite the fact that arachidonic acid supplements will "rapidly and safely modulate plasma and muscle fatty acid profile[s] and promote myogenic gene expression" in healthy, previously resistance-trained young men, it will not increase basal systemic or intramuscular inflammation. If you want to learn more about the way(s) ARA may dabble with your gains, I recommend revisiting the authors' previous paper "Emerging roles of pro-resolving lipid mediators in immunological and adaptive responses to exercise-induced muscle injury" (Markworth 2016).

|

| Want to Home-Brew Your Own 15x More Bioavailable Super-Curcumin? Buy Buttermilk and a Yogurt Starter Culture | learn how it works. |

Post-prandial stretching, on the other hand, is - as of yet - not proven to be a relevant factor in non-diabetic individuals.

Plus: Ploug, et al. have shown as early as in 1984 that stretching is only one of multiple ways in which muscle glucose uptake is increased by muscular wear and tear (contractions) - independent of insulin, by the way!

What? Oh, yes, arachidonic acid... Well, the previously cited real-world study by Peters shows that ARA "supplementation [at 1g/d does] not promote statistically greater gains in strength, muscle mass, or influence markers of muscle hypertrophy" (Roberts 2007) in 31 resistance-trained male subjects (22.1 ± 5.0 years, 180 ± 0.1 cm, 86.1 ± 13.0 kg, 18.1 ± 6.4% body fat) - or, you could argue, it's just as effective as corn oil | Comment ;-)

- Gurudut, Peeyoosha, and Abey P. Rajan. "Immediate effect of passive static stretching versus resistance exercises on postprandial blood sugar levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical trial." Journal of exercise rehabilitation 13.5 (2017): 581.

- Markworth, James F., Krishna Rao Maddipati, and David Cameron-Smith. "Emerging roles of pro-resolving lipid mediators in immunological and adaptive responses to exercise-induced muscle injury." Exercise immunology review 22 (2016).

- Markworth, James F., et al. "Arachidonic acid supplementation modulates blood and skeletal muscle lipid profile with no effect on basal inflammation in resistance exercise trained men." Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids (PLEFA) (2017).

- Nelson, Arnold G., Joke Kokkonen, and David A. Arnall. "Twenty minutes of passive stretching lowers glucose levels in an at-risk population: an experimental study." Journal of physiotherapy 57.3 (2011): 173-178.

- Park, Seong Hoon. "Effects of passive static stretching on blood glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus." Journal of physical therapy science 27.5 (2015): 1463-1465.

- Ploug, T., Henrik Galbo, and Erik A. Richter. "Increased muscle glucose uptake during contractions: no need for insulin." American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism 247.6 (1984): E726-E731.

- Roberts, Michael D., et al. "Effects of arachidonic acid supplementation on training adaptations in resistance-trained males." Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 4.1 (2007): 21.

- Teich, Trevor, et al. "Curcumin limits weight gain, adipose tissue growth, and glucose intolerance following the cessation of exercise and caloric restriction in rats." Journal of Applied Physiology (2017): jap-01115.