In two sequential studies, Harvey et al. investigated the effects, efficacy of, and mechanism behind "intermittent energy restriction" (IER), i.e. reducing your energy intake by a whopping 70% for two consecutive days while eating (a) an energy-sufficient Mediterranean diet (in study 1) and (b) an unrestricted low-carb (+high-protein) diet with portion control or as much 'clean' protein and fat as the subjects wanted on the on the other days (in study 2).

Learn more about fasting at the SuppVersity

So, what did the diets actually look like? As previously hinted at, Harvey et al. compared the IER approach to continuous dieting achieving the same 25% /week total energy deficit as the intermittent fasters in two sequential studies - both studies lasted for six months:

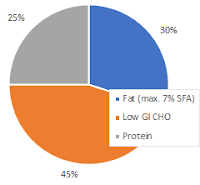

Study 1 included 50 pre-menopausal overweight or obese women and compared continuous dieting to intermittent energy restriction, i.e. 2 days of -70% followed by 5 days on a Mediterranean type diet (30% of energy from fat; [7% saturated, 15% monounsaturated and 7% polyunsaturated fatty acids], 45% low glycaemic load carbohydrate and 25% protein). On these days the subjects were yet not allowed to eat as much as they wanted, as long as they hit their macros, rater "[p]articipants were advised on maximal quantities of protein, carbohydrate and fat on these days and weekly guidance for treat foods (3 per week) and alcohol (14 units/week) to prevent over consumption" (Harvey 2018).![]()

Figure 1: Macronutrient composition of the "Mediterranean type diet" in study 1.

Important notice: We are not talking about what you'd call a true "ad-libitum" (=as much and as often as desired) but, at least, a very controlled approach to eating enough that was supposed to reduce the risk of overeating.

With study 1 being geared towards testing if IER works, at all (or rather at least as well as continuous dieting), it is study 2 that really addressed the initially mentioned issue of "rebound overconsumption of energy on unrestricted days" (Harvey 2018), because it included one group of subjects who were allowed to consume unlimited amounts of food on restricted days ... Well, as long as this food was lean meat, fish, eggs, tofu and unsaturated fats - basically, we are thus talking about an "ad libitum low[ish] carbohydrate diet"... but let's check out the details (I underlined relevant differences to study 1)

- Study 2 included 75 pre and post-menopausal women with overweight or obesity. The targeted caloric deficit per week was -25%. To achieve this deficit, the subjects consumed an energy-restricted low carbohydrate + high-protein diet (600–650 kcal/day, <50 g carbohydrate/day, 250g of protein). More specifically, subjects in both groups consumed...

"three servings of low-fat dairy foods, 4x80 g portions of low-carbohydrate vegetables and one portion of low-carbohydrate fruit, at least 1,170 ml of other low-energy fluids, and an over the counter multivitamin and mineral supplement" (Harvey 2018).

Now, the difference between group 1 and group 2 was that the former received the same advice on maximal portions of foods and treats to ensure participants did not overconsume as the IER group in study 1. Group 2, "was similar, but allowed unlimited lean meat, fish, eggs, tofu and unsaturated fats on restricted days" (Harvey 2018) - as far as portion sizes and total food intake are concerned, the subjects in the second group of the second study were thus on a true "ad libitum" low carbohydrate diet.

Take home message #1: Overeating is not an issue for overweight and obese women if (1) they go low carb and (b) restrict the type of foods they're allowed to eat "ad-libitum" on non-fasting days to lean meat, fish, eggs, tofu and unsaturated fats.

The above is also the main take-home message of a two-part study. Before I'll address the practical significance of the results in this articles bottom line, it is yet worth to look at the remaining findings of Harvey et al.'s latest paper:

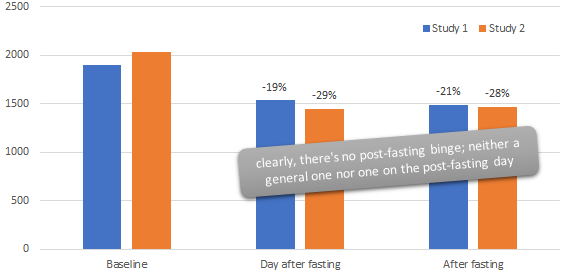

- The average study subject in study 1 (IER vs. continuous dieting) did not achieve the targeted 25%/week deficit. Rather than that, the 7-day food logs the scientists analyzed show that even their reported energy intake was only 19% lower compared with the allocated isoenergetic diet.

- The women in study 2 (LC-IER w/ portion control vs. 'ad-libitum') came close to the -25% target, when they followed the dietary prescription (study 2, group 1 | -21%), and surpassed it (-29%), when they followed the "lean protein + fat"-only approach on the ad-libitum days.

- As far as the fasting itself is concerned, 70% of women in study 1 and 79% in study 2 adhered to their individual fasting schedule and undertook consistent days of restriction each week (note: adherence was yet defined as consuming >50% of restricted days on the same 2 days each week - not very impressive, but achievable and thus realistic).

The pooled analysis of the data confirmed the most important rule of dieting: the best diet is always the one you or your clients will adhere to. It is thus not surprising that

"when studies were combined percentage weight loss at 3 months was −5.8 (−6.7 to −4.7) % in the consistent group and −7.4 (−8.7 to −6.2) % in the non-consistent group (p = .09)" (Harvey 2018).

With a p-value of 0.09, the adherence advantage did yet (somewhat surprisingly) not achieve statistical significance in the pooled (both studies, all groups) analysis (note: this may be due to the previously criticized way of defining adherence as doing >50% of the fasting days - with a stricter criterion, such as >75% of the fasting days, I am pretty confident that the difference would have been statistically significant).

Take home message #2: Intermittent energy restriction within the constraints of the dietary intervention used in the study at hand didn't trigger overeating even on the days immediately before and after restricted days, i.e. those days where you would expect psychological (before) and physiological (after) effects to promote overeating.

What is more important in view of the original research question, anyway, is that the scientists' diet-specific (IER vs. CON) analysis of the 7-day food logs the patients had to fill at 1, 3 and 4 months showed a general benefit of IER vs. continuous energy restriction, with patients undertaking IER exhibiting a spontaneous reduction in energy intake below their baseline reported intakes and the prescribed isoenergetic diet during all unrestricted days.

|

| Figure 3: Energy intake at baseline and on the different unrestricted days of intermittent energy restriction in Study 1 (n = 44) and Study 2 (n = 67) in kcal/day; %-ages indicate relative difference to baseline (Harvey 2018) |

Just to make that clear: Overeating didn't occur in any of the IER-groups - irrespective of whether the subjects practiced what I would like to call "mindful eating" (study 1, group 2 and study 2, group 1) or stuck to high protein + unsaturated fat on the five "ad-libitum" days per week. At least within the constraints of the two studies at hand, IER or "intermittent fasting" does, therefore, seem to have the added advantage of reigning in your food cravings, so that the small, but measurable deficit on the "unrestricted" days adds to the planned deficit on the fasting days... before you close this article and embark on your personal 2/5 diet experiment, though, I highly suggest you keep reading to understand what Harvey's studies really tell us.

The subjects diets were restricted in terms of (a) macros, (b) foods, and (c) portion sizes (and indirectly total energy intake). Study 2, group 1 came closer to what people think of when they read the aforementioned articles about the "magic of fasting". The subjects were indeed allowed to eat as much as they wanted, but they had to choose from a very limited repertoire of foods that were (a) high in protein, (b) low in carbohydrates, and (c) contained mostly if not only unsaturated fat. The classic overeating triggers like cake + ice cream, alternated with chips + pretzels, for example, were an absolute no-go for all three IER-groups.

So, yes, the authors are right, their studies show that you're not running the risk of overeating on the post-fasting (or any other non-fasting) day. They even suggest that there's even a certain "carry-over effect" that can be seen "across all unrestricted days in the food records including the days immediately before and after restricted days". And yes, Harvey et al. are also right to point out that this reduction in energy intake "is likely to be an important component contributing to the overall energy deficit and efficacy of IER for weight loss". What you must not forget, though, is that said benefit occurred in the context of extensive dietary changes (MED or low-carb + high-protein + whole foods) which took the foods we usually tend to overeat out of the equation.

Take home message #3: Beware of jumping to conclusions and overgeneralizing the results of the studies at hand! The subjects were exclusively female, overweight or obese and, most importantly: No one here ate as much as (s)he wanted of whatever (s)he wanted whenever (s)he felt like it.

So, yes: Intermittent fasting (2 fasting days per week) doesn't make you so hungry that you will automatically overeat the day after. In fact, in the two studies at hand, it even triggered a significant 19-29% reduction on what some people may misleadingly call the "ad-libitum" day... "misleadingly?", because none of the three IF protocols in the study at hand were "ad-libitum" as in "what you want, when you want, how much you want", i.e. the way people interpret "ad libitum" in the real world, where many dieters approach 2/5 routines as follows:"I starve myself for two days, then I return to my habitual junk-food diet and eat as much as I want." - That's not what the study tested, folks!The subjects in study 1, group 2 and their peers in study 2, group 1 were not really eating "ad-libitum" in the sense of "what and as much of it as they wanted".

|

| Training in the fasted state is no magic fat-loss bullet. Another study confirmed that very recently | more! |

So, yes, the authors are right, their studies show that you're not running the risk of overeating on the post-fasting (or any other non-fasting) day. They even suggest that there's even a certain "carry-over effect" that can be seen "across all unrestricted days in the food records including the days immediately before and after restricted days". And yes, Harvey et al. are also right to point out that this reduction in energy intake "is likely to be an important component contributing to the overall energy deficit and efficacy of IER for weight loss". What you must not forget, though, is that said benefit occurred in the context of extensive dietary changes (MED or low-carb + high-protein + whole foods) which took the foods we usually tend to overeat out of the equation.

|

| Remember this "refeeding study"? In essence, it is like the negative image of the two studies Harvey et al. report in the paper at hand. Where the subjects in Harvey's studies fasted for two days and ate "normal" for 5 days, the subjects in this older paper dieted for five days and ate normal for two days - both worked well, btw. | learn more |

Unfortunately, the results of this study cannot be generalized to (a) other populations such as lean individuals with much less body fat to use as fuel and/or the "real world", where most people (b) won't practice portion control or stick to a "lean protein + fat"-only approach on the ad-libitum days.

Previous studies do, however, suggest that humans in general (young, old, lean or fat) - even if they do overconsume food on the post-fasting days - end up in a caloric deficit when they fast intermittently. How's that? Well, while they do overeat on post-fasting days they still consume "much less energy than required to compensate for the energy deficit induced by the fast" (Johnstone 2002 | note: the lack of full compensation seems, as one would expect, to be more pronounced in overweight/obese vs. lean folks) | Comment on Facebook!

- Harvey, Jennifer, et al. "Intermittent energy restriction for weight loss: Spontaneous reduction of energy intake on unrestricted days." Food Science & Nutrition (2018).

- Johnstone, A. M., et al. "Effect of an acute fast on energy compensation and feeding behaviour in lean men and women." International journal of obesity 26.12 (2002): 1623.