Some swear by whole foods, others stick to special carbohydrate mixes, others again combine carbohydrates and protein and many simply grab the next best energy drink or supplement with an allegedly "science-based" formula. What is optimal, however, isn't just determined by the amount of energy it delivers. It's also influenced by the metabolic effects of the preworkout meal.

Learn more about carbohydrates at the SuppVersity!

When I look at the tabular overview of the studies, Ormsbee et al. reviewed in their latest paper, there is yet another factor that appears to have an even greater impact on the benefits of pre-workout meals / supplementation and that's timing! In the discussion of their results, the South African researchers write.

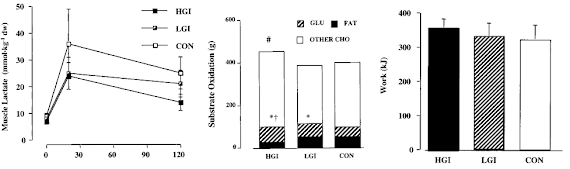

What both the 1-4h prior and the <60 min pre-exercise approach have in common is that they trigger an initial drop in blood glucose at the onset of the exercise period. Interestingly, the latter is more pronounced for shorter time-spans between the ingestion of the meal / nutrient supplement and the workout."The timing of CHO intake influences its metabolic effects. Indeed, insulin and blood glucose elevations are positively correlated with CHO meal proximity to exercise (Moseley. 2003). Studies in which CHO is consumed 1–4 h prior to exercise often report glucose and insulin levels declining to near-basal levels prior to exercise (Coyle. 1985; Kotsiopoulou. 2002; Chen. 2009).

Figure 1: Drop in glucose in well-trained cyclist on the onset of 30min cycling exercise after ingestion of 75g glucose or fructose or placebo (Koivisto. 1981)

Alternatively, when subjects consume CHO ≤60 min before exercise, insulin and blood glucose levels are reported to be elevated immediately prior to exercise (Koivisto. 1981; Chryssanthopoulos. 1994; Febbraio. 2000a,b)." (Ormsbee. 2014)

|

| If we go by the general trend in the studies,Ormsbee et al. reviewed, it appears as if you'd better leave 60min between your last meal and your workout if you want to benefit. |

In general, it's not necessary to consume "slow" carbs. Chen et al. for example observed performance increases with high, but not with low GI carbs ingested 2h before a workout (Chen. 2009); what Ormsbee et al. don't mention in their overview, tough, is that this worked only, because the subjects supplemented 2h before and during the workout.

Fat burning machines train low and compete high!?

Similarly, the evidence for the usefulness of high fat feeding immediately before a competition isn't there (Ormsbee. 2014). Rather than that many endurance athletes who follow a lowe(er) carbohydrate diet, "train low" and "compete high" - in this case "high" and "low" don't refer to the altitude, thought, but indicate training with a low carbohydrate intake and increasing the carbohydrate intake shortly before a competition. Some experts see this critically, though. Louise M. Burke, for example, writes:

"More recently, it has been suggested that athletes should train with low carbohydrate stores but restore fuel availability for competition (‘‘train low, compete high’’), based on observations that the intracellular signaling pathways underpinning adaptations to training are enhanced when exercise is undertaken with low glycogen stores. The present literature is limited to studies of ‘‘twice a day’’ training (low glycogen for the second session) or withholding carbohydrate intake during training sessions. Despite increasing the muscle adaptive response and reducing the reliance on carbohydrate utilization during exercise, there is no clear evidence that these strategies enhance exercise performance. Further studies on dietary periodization strategies, especially those mimicking real-life athletic practices, are needed." (Burke. 2010; my emphasis)In an article in the Journal of Sports Sciences Burke wrote with John A. Hawley, Stephen H. S. Wong & Asker E. Jeukendrup, the authors accordingly classify the "train low, compete high"-principle as principle with "equivocal evidence" (Burke. 2011).

But what about fat adapation and keto-athletes? Obviously Burke's position stands in contrast to papers by Volek, Noakes and Phinney who have recently repeated their conviction that "the shift to fatty acids and ketones as primary fuels when dietary carbohydrate is restricted could be of benefit for some athletes" (Volek. 2014), even though they still cannot provide the scientific evidence that would turn the "could" in the previously cited sentence into a "can".

More recent research again suggests that we may not even be dealing with an "either or" problem, here. In fact, an experiment Murakamiet al. conducted only recently would suggest:Could using fat and carbs, instead of fat or carbs increase performance even more?

The scientist from the Fukuoka University examined the performance effect of consuming either: (1) a high-fat meal 4 h pre-exercise + a placebo jelly 3 min before exercise (HFM + P); (2) a high-fat meal 4 h pre-exercise + maltodextrin jelly 3 min before exercise (HFM+ M); or (3) a high-CHO meal 4 h pre-exercise + placebo jelly 3 min before exercise (HCM + P).

The study was conducted after the subjects, eight male collegiate long-distance athletes, who engaged in physical training almost every day, had consumed an isocaloric, high-CHO diet for three days (2562 ± 19 kcal). The isocaloric test meals (1007 ± 21 kcal) were consumed 4 h before a standardized exercise test consisting of 80 min submaximal runing on a treadmill at each runner’s pre-determined lactate threshold (LT) speed.

|

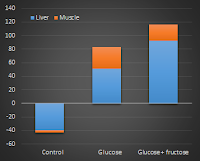

| Post-workout muscle glycogen resynthesis with glucose or glucose + fructose (Casey. 2000) |

"This suggests that CHO feeding subsequent to a HFM pre-exercise and three days of a proper CHO loading protocol can elicit an enhancement in the endurance performance of well-trained runners.[...] however, Murakami and colleagues did not include a HCM + M group, which raises questions about whether the HFM + M group performed longer primarily due to HFM [i.e. due to the extra fat] or rather as a result of the increased caloric consumption of maltodextrin immediately pre-exercise." (Ormsbee. 2014)It appears likely that this methodological issue renders the study results more or less worthless, because previous studies have found more or less unequivocally that fat and fat & carbohydrate supplements don't increase the exercise performance of endurance athletes:

- Okano, G., et al. (1996) who didn't find performance increases in response to the ingestion of a 30% carbohydrate, 61% fat and 9% protein meal 4h before an exercise test that consisted of cycling at 65% of the maximal oxygen consumption for the first 120 min of exercise, followed by an increased dose of 80 % V0_max,

- Rowlands et al. (2002) who found no benefits of consuming a high fat meal before a 50-km time trial, and

- Paul, et al. (2003) who found that even dosed at 1.3g/kg body weight a high fat meal has no effect on timetrial performance of 8 trained men.

Caffeine & protein, the bodybuilder's darlings

Both caffeine and protein have been shown to be useful for endurance athletes, but only the former, i.e. caffeine supplements will lead to significant performance increases.

"Regardless of an athlete’s genetic disposition, a dose of 3–6 mg of caffeine/kg of body weight has been shown to enhance performance in most individuals, with no further benefit from higher doses." (Ormsbee. 2014)For the latter, i.e. protein, the latest review clearly states that the contemporary evidence shows that

"[...] when carbohydrate supplementation was delivered at optimal rates during or after exercise, protein supplements provided no further ergogenic effect, regardless of the performance metric used." (McLellan. 2014)What protein supplements can do, though, is to speed up the glycogen resynthesis and glycogen hypersaturation after workouts (Morifuji. 20045) and contribute and "enhance skeletal muscle remodelling and stimulate adaptations that promote an endurance phenotype" (Moore. 2014).

|

| Post-Workout Glycogen Repletion - The Role of Protein, Leucine, Phenylalanine and Insulin. Plus: Protein & Carbs How Much do You Actually Need After a Workout? Learn more about PWO supplements |

The use of high fat supplements or additional fat in a pre-workout meal, on the other hand has no significant scientific backup that would suggest that it does anything, but shift the substrate metabolism from high glucose to medium glucose & medium fat oxidation. Protein and caffeine, on the other hand can help. Yet only caffeine (0.3-0.6mg/kg) is something that will have immediate performance enhancing effects, when it's consumed before a workout. Protein, on the other hand, should be consumed in the post-workout phase instead | Comment on Facebook!

Ah, and yes: (A) You can use bananas, mashed potatoes and other whole foods instead of sugar drinks. And (B) These suggestions are also valid for strength trainees, who like their workouts (1) intense, (2) long (>35 minutes) and (3) with only 60s of rest between sets. If you are one of the "let's take a break" guys who spends 2h in the gym doing ten sets of bench presses and a lot of talking, you better spare yourself the carbohydrate load before the workout.

- Burke, L. M. "Fueling strategies to optimize performance: training high or training low?." Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 20.s2 (2010): 48-58.

- Burke, Louise M., et al. "Carbohydrates for training and competition." Journal of Sports Sciences 29.sup1 (2011): S17-S27.

- Casey, Anna, et al. "Effect of carbohydrate ingestion on glycogen resynthesis in human liver and skeletal muscle, measured by 13C MRS." American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism 278.1 (2000): E65-E75.

- Chen, Y. J., et al. "Effects of glycemic index meal and CHO-electrolyte drink on cytokine response and run performance in endurance athletes." Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 12.6 (2009): 697-703.

- Coyle, Edward F., et al. "Substrate usage during prolonged exercise following a preexercise meal." J Appl Physiol 59.2 (1985): 429-33.

- Chryssanthopoulos, C., L. C. Hennessy, and C. Williams. "The influence of pre-exercise glucose ingestion on endurance running capacity." British journal of sports medicine 28.2 (1994): 105-109.

- Febbraio, Mark A., et al. "Effects of carbohydrate ingestion before and during exercise on glucose kinetics and performance." Journal of Applied Physiology 89.6 (2000a): 2220-2226.

- Febbraio, Mark A., et al. "Preexercise carbohydrate ingestion, glucose kinetics, and muscle glycogen use: effect of the glycemic index." Journal of Applied Physiology 89.5 (2000b): 1845-1851.

- Kotsiopoulou, Christina, and Veronica Vleck. "The effect of a high carbohydrate meal on endurance running capacity." International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism 12 (2002): 157-171.

- Koivisto, Veikko A., Sirkka-Lisa Karonen, and Esko A. Nikkila. "Carbohydrate ingestion before exercise: comparison of glucose, fructose, and sweet placebo." J Appl Physiol 51.4 (1981): 783-787.

- McLellan, Tom M., Stefan M. Pasiakos, and Harris R. Lieberman. "Effects of Protein in Combination with Carbohydrate Supplements on Acute or Repeat Endurance Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review." Sports Medicine 44.4 (2014): 535-550.

- Moseley, Luke, Graeme I. Lancaster, and Asker E. Jeukendrup. "Effects of timing of pre-exercise ingestion of carbohydrate on subsequent metabolism and cycling performance." European journal of applied physiology 88.4-5 (2003): 453-458.

- Moore, Daniel R., et al. "Beyond muscle hypertrophy: why dietary protein is important for endurance athletes 1." Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 39.999 (2014): 1-11.

- Morifuji, Masashi, et al. "Dietary whey protein increases liver and skeletal muscle glycogen levels in exercise-trained rats." British journal of nutrition 93.04 (2005): 439-445.

- Murakami, Ikuma, et al. "Significant effect of a pre-exercise high-fat meal after a 3-day high-carbohydrate diet on endurance performance." Nutrients 4.7 (2012): 625-637.

- Okano, G., et al. "Effect of 4h preexercise high carbohydrate and high fat meal ingestion on endurance performance and metabolism." International journal of sports medicine 17.07 (1996): 530-534.

- Ormsbee, Michael J., Christopher W. Bach, and Daniel A. Baur. "Pre-Exercise Nutrition: The Role of Macronutrients, Modified Starches and Supplements on Metabolism and Endurance Performance." Nutrients 6.5 (2014): 1782-1808.

- Paul, David, et al. "No effect of pre-exercise meal on substrate metabolism and time trial performance during intense endurance exercise." International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism 13 (2003): 489-503.

- Rowlands, David S., and Will G. Hopkins. "Effect of high-fat, high-carbohydrate, and high-protein meals on metabolism and performance during endurance cycling." International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism 12 (2002): 318-335.

- van Loon, Luc JC, et al. "Maximizing postexercise muscle glycogen synthesis: carbohydrate supplementation and the application of amino acid or protein hydrolysate mixtures." The American journal of clinical nutrition 72.1 (2000): 106-111.

- Volek, Jeff S., Timothy Noakes, and Stephen D. Phinney. "Rethinking fat as a fuel for endurance exercise." European journal of sport science ahead-of-print (2014): 1-8.

- Whitley, Helena A., et al. "Metabolic and performance responses during endurance exercise after high-fat and high-carbohydrate meals." Journal of Applied Physiology 85.2 (1998): 418-424.