Scientists from the from the Newcastle University just published the results of an interesting experiment, in which they aimed to investigate whether three groups of obese men, exposed to different levels of negative energy balance (fasting, very low calorie diet (VLCD, 2.5MJ/day) and low-calorie diet (LCD, 5.2MJ/day)) in experimental controlled conditions, were characterised by distinct changes in resting and total EE after losing a similar amount of body weight (5% and 10%WL).

As the scientists point out, "[t]he study also provided the opportunity to test if the rate of WL and weight lost as FFM [fat free mass] were associated with the level of adaptive thermogenesis" (Siervo. 2015). The significance of the results for athletes and wanna-be athletes should thus be obvious.

Do you have to worry about fasting when your're dieting!?

The actual energy intake (EI) of the subjects was measured daily. While the participants in the starvation group had access to water only, the diets of the other groups contained 32% of the energy as protein, 35% as carbohydrate and 33% as fat. More specifically,"[D]uring the 6-day baseline period subjects consumed a fixed maintenance diet (13% protein, 30% fat and 57% carbohydrate). After the 7-day baseline period, each group followed the specific diet to lose 5% and 10% of their baseline body weight. However, the duration of the fasting was of 6 days as ethical constraint allowed to fast subjects to lose 5% of their baseline body weight. The duration of the WL phases to achieve a 10%WL was of 3 and 6 weeks for the VLCD and LCD groups, respectively. Throughout the study, participants were residential in the Human Nutrition Unit at the Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health (RINH), Aberdeen, UK.

Figure 1: Macronutrient intake in grams in the 3 diet groups (Siervo. 2015)

All food and drinks consumed by each participant during the study were supplied by the dietetics staff in the Unit. The participants were requested not to undertake any other strenuous physical activity during the study and they were asked to record their individual exercise sessions" (Siervo. 2015).

- the LCD weighed 1260g, with an energy content of 5.2kJ/g coming from protein 50.3g (17%), carbohydrate 155.7g (50%), and fat 45.4g (33%), while

- the VLCD weighed 642g, with an energy concent of 2.55kJ/g coming from protein 49.4g (32%), carbohydrate 52.8g (35%), and fat 23.1g (33%) and was thus - in science terms - a high "protein diet", because it contained >30% of the energy from protein.

The resting energy expenditure (REE) was measured at baseline and at the end of each WL phase (5% and 10%WL) by indirect calorimetry over 30–40 min using a ventilated hood system (Deltatrac II, MBM-200, Datex Instrumentarium Corporation, Finland).

|

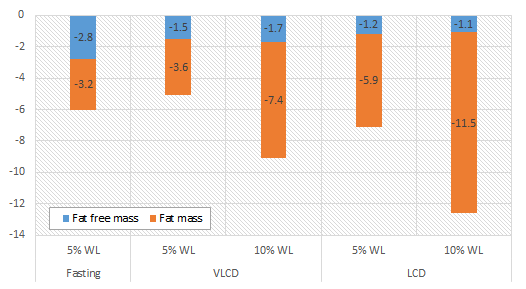

| Figure 2: Changes in body composition in the three diet groups according to weight loss (Siervo. 2015). |

Women watch out! It is not just possible, but in view of the association between the magnitude of daily energy deficit and the frequency of menstrual disturbances (Williams. 2015), women may see significantly more more side effects on harsh (fasting) diets.

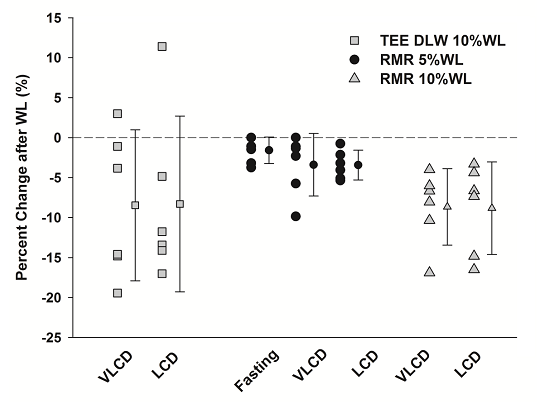

What is far more important, though, is the fact that the allegedly "sanest" way of dieting, i.e. the LCD (=moderate deficit), produced the most significant fat mass loss. Accordingly, the "slow" diet had the upperhand in terms of fat free mass (FFM) losses, as well: "The fraction of FFM to total WL after 5%WL was 46, 30 and 18% for the fasting, VLCD and LCD groups respectively. At 10% WL, the VLCD losses were 20% FFM and 80% FM compared with 9% FFM and 91% FM in the LCD group (Siervo. 2015).Against that background it's quite surprising that (a) the VLCD and LCD showed a similar degree of metabolic adaptation for total EE (VLCD=-6.2%; LCD=-6.8%) and that (b) the metabolic adaptation for resting EE was greater in the LCD (-0.4MJ/day, -5.3%) compared to the VLCD (-0.1MJ/day, -1.4%) group.

Likewise noteworthy: The resting EE did not decrease after short-term fasting and no evidence of adaptive thermogenesis (+0.4MJ/day) was found after 5%WL. The rate of WL was inversely associated with changes in resting EE (n=30, r=0.-42, p=0.01).

Eventually, it may thus seem that the study at hand would confirm what we already know: Slow and steady is best, ... and that's true, but the fact that "slow and steady" produces the greatest reduction in resting metabolic rate makes me question whether the weight rebound after longer, but less severe dieting phases is actually smaller or not. Previous studies suggested there's no difference, but these studies used different protocols and stand in contrast to a plethora of studies like Sénéchal et al. (2012 | learn more). Whether it would be the same for the study at hand is thus questionable | Comment on Facebook!

- Siervo, Mario, et al. "Imposed rate and extent of weight loss in obese men and adaptive changes in resting and total energy expenditure." Metabolism (2015): Accepted Article.

- Sénéchal, Martin, et al. "Effects of rapid or slow weight loss on body composition and metabolic risk factors in obese postmenopausal women. A pilot study." Appetite 58.3 (2012): 831-834.

- Tremblay, A., et al. "Adaptive thermogenesis can make a difference in the ability of obese individuals to lose body weight." International journal of obesity 37.6 (2013): 759-764.

- Williams, Nancy I., et al. "Magnitude of daily energy deficit predicts frequency but not severity of menstrual disturbances associated with exercise and caloric restriction." American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 308.1 (2015): E29-E39.