![]() |

| In hypoxia you still have to work out intensely & consistently to get shredded. |

This is not the first time you read about the almost marvelous effects a

low oxygen environment can have on the adaptive response to exercise, but after reading it, you will hopefully agree that it was one of the most interesting SuppVersity articles about

hypoxia.

The article discusses the results of a recent study from the

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research by Yan et al. In said study, the authors tested the effects of different levels of systemic hypoxia on the hormonal responses, strength, and body composition to 5-week resistance training.

![]()

The EPO Effect of Low O2

![]()

Bigger Biceps W/ Hypoxia

![]()

HIIT³ in Hypoxia = Über-HIIT?

![]()

Low Oxygen ➲ Low Body Fat

![]()

Lower Oxygen to Get Jacked

![]()

Hypoxia for Rapid Injury Recovery

To this ends, Yan et al. recruited twenty-five "physically active" male subjects with previous resistance training experience and randomly assigned them to one out of 3 experimental groups that performed 10 sessions (2 sessions per week) of barbell back squat (10 repetitions, 5 sets, 70% 1 repetition maximum [RM]) under

- normoxia, i.e. in a regular gym (NR, FiO2 = 21%), or

- severe (HH) or moderate (HL) hypoxia (HL, FiO2 = 16%; HH, FiO2 = 12.6%).

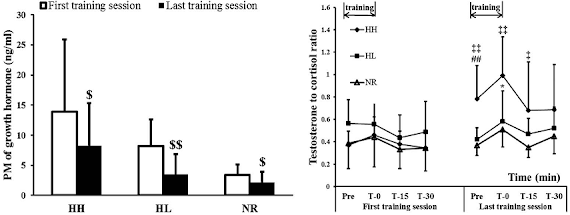

Serum growth hormone (GH), testosterone (T), and cortisol (C) concentrations were measured before (Pre) and at 0 (T-0), 15 (T-15), 30 (T-30) minutes after exercise in the first and last training sessions. The subjects' one repetition maximum (1-RM), their isometric knee extension, isometric leg press (LP), and body composition were evaluated before and after the protocol.

![]() |

| Figure 1: Hormonal response to resistance training under normal or reduced oxygen conditions; inerestingly, the effects on the testosterone / cortisol ratio increased, while those on GH decreased over time (Yun. 2015). |

As you can see in

Figure 1, the hormonal response the scientists observed during the first and last sessions in hypoxia foreshadowed the significant differences in the adapative response Yun et al. observed. To be more specific, the benefits materialized during the post-tests in form of significant improvements in isometric LP strength and an exclusively significant increase in lean body mass in the hypoxia groups (meaning the increase in the normoxia group was not significant).

But you recently wrote that the hormonal response doesn't matter! Yes, I did. Actually, that's not even long ago (

read up on it), but who said that the changes you see in

Figure 1 mechanistically caused the increased adaptive response? That must have been the little bro in your ear, because I certainly didn't do so. With regard to growth hormone, we need to be careful, anyway. In the year 2000, Raastad et al (2000) already demonstrated that the growth hormone response to one and the same resistance training protocol is highly individual with both responders and nonresponders. Furthermore, the GH response has been shown to increase with intensity and glycogen demands and the latter are obviously increased when a lack of oxygen in the blood reduces the efficacy of the citric acid cycle. The study at hand does therefore not contradict the results of the study at hand that Ho et al. didn't find similar effect on GH with a low-intensity resistance training protocol in normoxia vs. hypoxia (Ho. 2014). In fact, the differential response would rather support the hypothesis that the different hormonal response is a correlate, not a trigger of the improved adaptational response in the Yun study.

In view of the fact that we are dealing with a

moderate-intensity resistance training program, the former is as unsurprising as the significant isometric strength increases and lean mass changes in hypoxia are surprising.

![]() |

| Figure 2: Rel. Changes in strength and body composition over the course of only 5 weeks of training (Yan. 2015); please note that the absolute reduction in BF% was only 2% in the hypoxia and 1% in the normoxia group/s. |

Whether these effects (see

Figure 2) were in anyway mechanistically related to the significantly greater GH responses in the hypoxic training groups, however, remains questionable (see light blue box). The increased GH response could after all be a mere correlate of a different underlying mechanism that triggers both - the accelerated adaptive processes, subsequently increased gains and + fat lass and the temporarily elevated growth hormone levels. This hypothesis is further supported by the lack of differences between the training effects in the HL and HH group. If those were triggered by the observed acute changes in the so-called "anabolic hormones", the more beneficial testosterone to cortisol ratio (see

Figure 1) would have had to trigger a greater adaptive response in the HH group. The fact that it didn't is quite revealing. After all, the testosterone to cortisol ratio is still regarded as the most important marker of anabolism by the average bodybuilding forum visitor.

![]() |

| The mask on the right does not simulate training in hypoxia and cannot be expected to help effortlessly shed 11% of body fat as it was observed in a 2013 study in trained athletes. |

Ah... and now that we are already talking about the things people write in fitness forums, I should maybe mention that the "fitness masks" with which you look pretty much like Hannibal Lecter can

not replace a hyperbaric chamber or a mask with separate low O2 air supply. Why? The masks make it harder to breath. That has a certain training effect, because it trains the diaphragm, but this effect is (a) much more pronounced in (relatively) untrained individuals than in athletes and (b) and achieved by totally different mechanisms (Stuessi. 2001), of which we cannot assume that they have the same extended (beyond the training session) metabolic effects that make "true" hypoxia so effective.

Bottom line: Even though the results of the study at hand are impressive, there's little doubt that training at high altitudes and in low oxygen environments is rather an endurance athlete than a strength athlete thing. If you scrutinize the data in

Figure 2, the existing benefits in terms of size and strength gains are by no means as huge as the effects you see in endurance athletes in response to altitude camp training.

![]() |

| Figure 3: In a very similar study, Kon et al (2015) have recently demonstrated significant improvement in muscular endurance and a potent effect on muscular angiogenesis (the formation of new capillaries), but no significant extra-strength / -mass gains in response to 8wks training in hypoxia (14.4% oxygen). |

This thesis, by the way, is supported by data from another recent 8-week RT-study by Kon et al. (2015) who found significant differences only for the muscular endurance (see

Figure 3) and the level of VEGF, a protein that is responsible for improving the capillarization of skeletal muscle - both likewise rather endurance-specific benefits. And while this doesn't mean that gymrats cannot benefit from training in hypoxia, it does mean that you don't have to be furious that the owner of your local gym is to cheap to buy the equipment that would be necessary to reduce the oxygen levels beyond what the hundreds of sweating trainees will do ;-) |

Comment!

References:

- Ho, Jen-Yu, et al. "Effects of acute exposure to mild simulated hypoxia on hormonal responses to low-intensity resistance exercise in untrained men." Research in Sports Medicine 22.3 (2014): 240-252.

- Kon, Michihiro, et al. "Effects of systemic hypoxia on human muscular adaptations to resistance exercise training." Physiological reports 2.6 (2014): e12033.

- Raastad, Truls, Trine Bjøro, and Jostein Hallen. "Hormonal responses to high-and moderate-intensity strength exercise." European journal of applied physiology 82.1-2 (2000): 121-128.

- Stuessi, Christoph, et al. "Respiratory muscle endurance training in humans increases cycling endurance without affecting blood gas concentrations." European journal of applied physiology 84.6 (2001): 582-586.

- Yan, Bing, et al. "Effects of Five-Week Resistance Training in Hypoxia on Hormones and Muscle Strength." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 30.1 (2016): 184-193.