|

| Are NSAIDs over-the-counter anabolics from the pharmacy next door? |

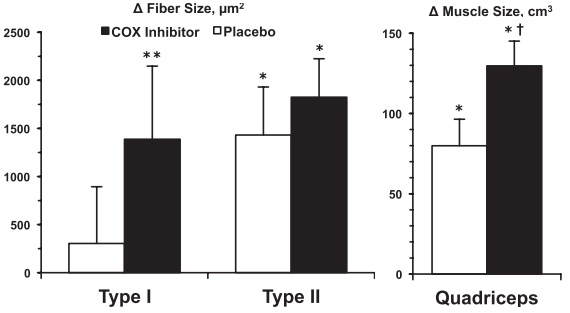

It is thus neither guaranteed, nor likely that a young man or woman would see the same 28% extra-increase in type I fiber and 11% extra-increase in type II fiber diameter, Trappe et al. describe in their soon-to-be-published paper in the journal of the Gerontological Society of America (Trappe. 2016).

The link to hormesis research is far from being straight-forward

Unfortunately, the results of the few studies we have, are conflicting (Schoenfeld. 2012; see Table 1) - with one showing benefits and two showing no effect at all. The purpose of Trappe's latest study was thus to (a) simply gather more evidence and (b) investigate the mechanism behind the changes that were observed in previous studies. Or, as the scientists put it "whether the underlying mechanism regulating this effect was specific to Type I or Type II muscle fibers" (Trappe. 2016).

|

| Table 1: Summary of human studies investigating the effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug consumption on muscle hypertrophy (Schoenfeld. 2012). |

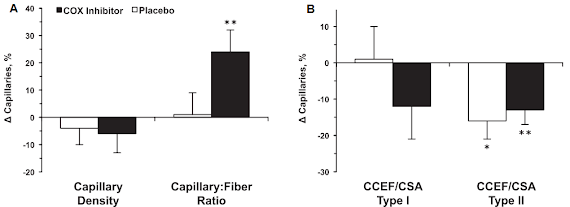

"All participants completed a progressive resistance exercise training program of bilateral knee extension that was designed to hypertrophy and strengthen the m. quadriceps femoris, using a protocol employed for several previous investigations in our laboratory. Each participant was scheduled for resistance training three times per week over the 12 weeks for a total of 36 sessions on an isotonic knee extension device (Cybex Eagle, Medway, MA). All sessions were supervised by a member of the research team. Each session was separated by at least 1 day and consisted of 5 minutes of light cycling(828E, Monark Exercise AB, Vansbro, Sweden), two sets of five knee extensions at a light weight, followed by three sets of 10 repetitions with 2 minutes of rest between sets. Training intensity was based on each individual’s one repetition maximum (1RM) and adjusted during the training based on each individual’s training session per formance and biweekly 1RM" (Trappe. 2016).The compliance of the subjects of this double-blinded study is described as excellent. Therefore, we can assume that the significance of the results of the scientists' analysis of muscle samples that were examined for Type I and II fiber cross-sectional area, capillarization, and metabolic enzyme activities (glycogen phosphorylase, citrate synthase, β-hydroxyacyl-CoA-dehydrogenase) is high.

|

| Figure 1: Pre-/post comparison on fiber (according to fiber type) and muscle size (Trappe. 2016). |

|

| Schematic of the prostaglandin (PG) producing cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway and specific receptors that influence growth and atrophy in skeletal muscle (Trappe. 2013b). |

In addition, the authors point out that previous evidence suggests an "additional mechanism for the COX inhibitor–induced supplemental growth, working through PGF2α receptor and protein synthesis upregulation" (Trappe. 2016; referring to Trappe. 2013a,b).

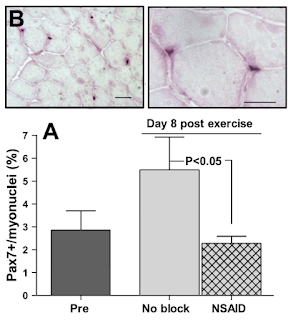

Why only in the elderly? Well based on previous research, there's in fact good reason to doubt that similar benefits would have been observed in younger individuals. The hitherto published results in young people are mixed. A possible explanation for that would be the previously observed "impairment of satellite cell activity" (Schoenfeld. 2012) in response to chronic NSAID consumption - a side effect that may turn out to be detrimental in the long(er)-term, because unlike older individuals, in whom the satellite cell function is compromised, already (Thornell. 2011), young people's long-term gains appear to rely on the myostatin lowering recruitement of additional myonuclei.

Overall, the potential negative effects on satellite cell activity and thus long-term muscle growth, the lack of convincing evidence of benefits in younger individuals and, for young and old alike, the negative side effects of chronic NSAID use on your tendons, gut, kidney and other organs are three good reasons I certainly don't advise to seriously consider "supplementing" NSAIDs daily to augment your muscle gains | Comment on Facebook!

- Mikkelsen, U. R., et al. "Local NSAID infusion inhibits satellite cell proliferation in human skeletal muscle after eccentric exercise." Journal of applied physiology 107.5 (2009): 1600-1611.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J. "The Use of Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for exercise-induced muscle damage." Sports medicine 42.12 (2012): 1017-1028.

- Standley, R. A., et al. "Prostaglandin E 2 induces transcription of skeletal muscle mass regulators interleukin-6 and muscle RING finger-1 in humans." Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids (PLEFA) 88.5 (2013): 361-364.

- Trappe, Todd A., and Sophia Z. Liu. "Effects of prostaglandins and COX-inhibiting drugs on skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise." Journal of Applied Physiology 115.6 (2013a): 909-919.

- Trappe, Todd A., et al. "Prostaglandin and myokine involvement in the cyclooxygenase-inhibiting drug enhancement of skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults." American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 304.3 (2013b): R198-R205.

- Trappe, Todd A., et al. "COX Inhibitor Influence on Skeletal Muscle Fiber Size and Metabolic Adaptations to Resistance Exercise in Older Adults." J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2016): Advance Access publication January 27, 2016.

- Thornell, Lars-Eric. "Sarcopenic obesity: satellite cells in the aging muscle." Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care 14.1 (2011): 22-27.