|

| Are you young and healthy? Then, high-dose NSAIDs may ruin your quad-gainz. |

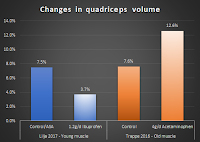

In fact, a relatively recent study by Mackey et al. (2016) observed beneficial effects on muscle repair in young men. And an even more positive image of NSAIDs emerges if you read Trappe et al.'s 2016 study in which they observed significant increases in muscle gains in older trainees.

Read about exercise- and nutrition-related studies in the SuppVersity Short News

In Schoenfeld's 2012 meta-analysis the three human trials, investigating the effects of NSAIDs on skeletal muscle hypertrophy that were available at that time seem to confirm the notion that the use of the prostaglandin-blocking COX-enzyme inhibitors won't impair your gains: while two of the study produced a null result (Krentz 2008; Petersen 2011), the other one, once more a study by Trappe et al. (2011), recorded a significant increase in muscle hypertrophy in the elderly subjects of the study.What does the latest study on hypertrophy tell us?

If the previously phrased hypothesis (old = benefits, young = detriments) holds true, the result of the most recent investigation into the effects of NSAIDs on skeletal muscle hypertrophy which was conducted by Mats Lilja and colleagues from the Karolinska Institutet and the Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, in young, healthy men and women (aged 18-35 years) should yield a null or a negative result - and that's indeed what you can see in Figure 2.

|

| Figure 2: The latest study by Lilja et al. observed a significant negative effect of high dose ibuprofen on hypertrophy. |

- consumed either ibuprofen (IBU; 1200 mg; n=15 - consumed in form of 3 separate 400mg doses at 8am, 2pm and 8pm) or a placebo, in this case acetylsalicylic acid aka aspirin (ASA; 75 mg; n=16 - consumed in the AM) at a dosage that was chosen low enough to assume that it won't mess with the study outcomes (if it did, it would only diminish the inter-group difference, so even if it did, the results of the study imply that NSAIDs impair muscle gains in young, healthy individuals), daily, and ...

- performed 20 leg workouts consisting of 4 × 7 maximal repetitions on a flywheel device (2 min rest) with one leg and 4 × 8–12 repetitions to failure a "weight stack" machine, of which I assume it was a leg extension device, with the other leg,

|

| With a sign. lower dosing (1x400mg IBU only on workout days) Krentz et al. (2008) didn't observe ill effects on gains/strength in a six-week 5d/wk biceps training study. |

A difference in training volume was observed neither in the study at hand nor in previous studies (where it was tested) - including those in older subjects that showed significant beneficial effects of NSAIDs on skeletal muscle hypertrophy such as Trappe et al. 2011 and 2016.

What's / what are the mechanism(s)?

The problem about identifying the underlying mechanisms is that Lilja et al.'s extensive molecular analyses found only one statistically significant inter-group difference that could potentially explain the previously described detrimental effects of IBU on size and, to a lesser extent, strength gains: the sign. reduced mRNA expressions of IL-6 (P<0.0001) in response to high dose ibuprofen treatment.

|

| Figure 3: Changes in IL-6 (left), COX1, COX2, PGF2-alpha, and p70S6K mRNA/protein expression (Lilja 2017). |

There's clearly need for future research: While the hormesis theory seems to explain the fundamental difference between the hypertrophy response of young and aged muscle upon NSAID-and acetaminophen-administration (the non-NSAID painkiller has also been shown to suppress the age-induced increase in ROS | Kakarla 2010) in the previously referenced studies, it is necessary to confirm that its predictions hold true in overtrained subjects or people who suffer from diseases that result in chronic inflammation. At least the latter should benefit from NSAIDs, as well.

While Lilja et al. speculate that they may have missed relevant signaling proteins or potential effects on satellite cells (note: a previous study shows that IBU expedites satellite cell recruitment, so that's very unlikely), I believe it's better to focus on the previously mentioned reduction in IL-6 - a reduction I would like to interpret as evidence of an overall reduced inflammatory/stress response, which could (a) impair the hormetic response to exercise in young individuals and thus explain the reduced hypertrophy in the study at hand (see Figure 2, 'NSAIDs in young individual'), and (2) reduce the already chronically elevated levels of of inflammation in aged muscles (Roubenoff 2003) to a tolerable level within the adaptation zone (see Figure 4, 'NSAIDs in old individuals') and could thus explain the increased hypertrophy Trappe et al. (2011) observed in their study in older individuals.insulin sensitivity) and training (hypertrophy) effects of exercise.

Even though the study at hand did not measure the concentration of reactive oxygen specimen (ROS), we know that NSAIDs in general, and IBU in particular, can reduce the formation of ROS in response to exercise (Pizza 1999). Furthermore, ROS has been shown to directly stimulate the release of IL-6 (Kosmidou 2002), of which we do know that it was significantly reduced with IBU in Lilja's most recent study.

Accordingly it seems logical to assume that a reduced ROS response is responsible for the reduced hypertrophy and strength adaptation - two auxiliary, but still important features of optimal health of which Ristow and Schmeisser (2014), in turn, have long been arguing that it has an inverse-U-shaped relationship with ROS / inflammatory processes as I've sketched it in Figure 4.

Even though the study at hand did not measure the concentration of reactive oxygen specimen (ROS), we know that NSAIDs in general, and IBU in particular, can reduce the formation of ROS in response to exercise (Pizza 1999). Furthermore, ROS has been shown to directly stimulate the release of IL-6 (Kosmidou 2002), of which we do know that it was significantly reduced with IBU in Lilja's most recent study.

Accordingly it seems logical to assume that a reduced ROS response is responsible for the reduced hypertrophy and strength adaptation - two auxiliary, but still important features of optimal health of which Ristow and Schmeisser (2014), in turn, have long been arguing that it has an inverse-U-shaped relationship with ROS / inflammatory processes as I've sketched it in Figure 4.

Warning: Do not take NSAIDs day in, day out, as if they were creatine. While the latter is often falsely portrayed as "dangerous steroid" in the media, the sides of aspirin, ibuprofen and co are hardly talked about and that despite the fact that they can, when taken chronically, severely damage the stomach lining, hurt the kidney, cause CNS-related side effects and allergies - in particular if they are taken at high dosages, as they are needed for the beneficial effects that were observed in the elderly. Short-term, i.e. to acutely treat pain (10 days or less), they do yet have a better safety profile than some non-evidence websites may try to tell you (Aminoshariae 2016).

In short: While young people risk ending up too far on the left-hand side of the "optimal ROS concentration" / "optimal level of inflammation" (Figure 4, green) when they consume high doses of NSAIDs on a daily basis (lower doses and less frequent administration may have correspondingly less pronounced effects), older people may benefit from the ability of NSAIDs to reduce the age-induced increase in inflammation (Figure 4, orange) and bring the inflammation levels closer to the dashed green line that represents the optimal degree of inflammation in Figure 4... ah, obviously this is just a hypothesis; unlike the differential effects in young and old subjects, by the way | Comment!

References:- Aminoshariae, Anita, James C. Kulild, and Mark Donaldson. "Short-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and adverse effects: an updated systematic review." The Journal of the American Dental Association 147.2 (2016): 98-110.

- Diaz, Arturo, John Varga, and Sergio A. Jimenez. "Transforming growth factor-beta stimulation of lung fibroblast prostaglandin E2 production." Journal of Biological Chemistry 264.20 (1989): 11554-11557.

- Haddad, Fadia, et al. "IL-6-induced skeletal muscle atrophy." Journal of applied physiology 98.3 (2005): 911-917.

- Kakarla, Sunil K., et al. "Chronic acetaminophen attenuates age-associated increases in cardiac ROS and apoptosis in the Fischer Brown Norway rat." Basic research in cardiology 105.4 (2010): 535-544.

- Kosmidou, Ioanna, et al. "Production of interleukin-6 by skeletal myotubes: role of reactive oxygen species." American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 26.5 (2002): 587-593.

- Krentz, Joel R., et al. "The effects of ibuprofen on muscle hypertrophy, strength, and soreness during resistance training." Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 33.3 (2008): 470-475.

- Lilja, Mats, et al. "High‐doses of anti‐inflammatory drugs compromise muscle strength and hypertrophic adaptations to resistance training in young adults." Acta Physiologica (2017).

- Mackey, Abigail L., et al. "Activation of satellite cells and the regeneration of human skeletal muscle are expedited by ingestion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication." The FASEB Journal (2016): fj-201500198R.

- Pizza, F. X., et al. "Anti-inflammatory doses of ibuprofen: effect on neutrophils and exercise-induced muscle injury." International journal of sports medicine 20.02 (1999): 98-102.

- Ristow, Michael, and Kathrin Schmeisser. "Mitohormesis: promoting health and lifespan by increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS)." Dose-Response 12.2 (2014): dose-response.

- Roubenoff, Ronenn. "Catabolism of aging: is it an inflammatory process?." Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care 6.3 (2003): 295-299.

- Steinbacher, Peter, and Peter Eckl. "Impact of oxidative stress on exercising skeletal muscle." Biomolecules 5.2 (2015): 356-377.

- Trappe, Todd A., et al. "Effect of ibuprofen and acetaminophen on postexercise muscle protein synthesis." American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 282.3 (2002): E551-E556.

- Trappe, Todd A., et al. "Influence of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on skeletal muscle adaptations to resistance exercise in older adults." American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 300.3 (2011): R655-R662.

- Trappe, Todd A., and Sophia Z. Liu. "Effects of prostaglandins and COX-inhibiting drugs on skeletal muscle adaptations to exercise." Journal of Applied Physiology 115.6 (2013): 909-919.

- Trappe, Todd A., et al. "COX Inhibitor Influence on Skeletal Muscle Fiber Size and Metabolic Adaptations to Resistance Exercise in Older Adults." J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2016): Advance Access publication January 27, 2016.