|

| Your hedonic response usually isn't a good food guide |

For a good reason, as I should say. Being written for the average inhabitant of the Western Obesity Belt, the authors of these articles willingly accept that their readers will (mis-)understand them as a soothing incentive not just to maintain their overtly hedonistic lifestyle, but to top it off with an extra portion of super-sized chocolate cookies... I mean, it's "chocolate", right? So it's good for you, even the latest science says so, right? And not just that, even the NY Times writes chocolate is a "health food" (NY Times. 2009)

Right, science says: Chocolate is good for you! But when we look closer, the chocolate that is good for you has little to no resemblance to the candy bars the lady in the photo is savoring. What scientific research really says is that small amounts of real chocolate and somewhat larger amounts of artificially pimped high polyphenol chocolate are good for you; and it goes without saying that this constraint excludes 99% of the chocolate and allegedly "chocolate" containing foods that are sold at supermarkets and even health food stores.

Most of the "chocolate" on the market makes you fat, diabetic, hypertensive, and forgetful

Yes, you hear me right. Regular (milk) chocolate with a phenol content of <5 gallic acid equivalents (that's the unit you use to measure the total amount of polyphenols in a given product), and the average dark chocolate with a phenol content of <15 gallic acid equivalents have the same pro-obesogenic effect as the low-polyphenol chocolate in a recent study by Farahat et al. (2014).

|

| Figure 1: The unfortunate truth is, for most people "bad things" happen, when they eat more chocolate. |

You can learn more about chocolate at the SuppVersity

Real chocolate, on the other hand, will nor make you fat, improve your blood lipids, ...

I guess before I will give away the actual three reasons, why eating real chocolate (in moderation), may be a good idea, it's worth defining the word "real" which, in this case, refers to the chocolate and polyphenol content of the brownish bars and powders you can buy in the supermarket, grocery and specialty stores.

And as the tabular overview of the polypenol content and total antioxidant activity in Table 1 goes to show you, the latter, i.e. the specialty store, may not even always be the best choice. With a total phenol content of 26-29 gallic acid equivalents, the cheap baking chocolate is after all a viable alternative to the expensive organic cacao powder, of which I don't have to tell you that it will be hard to "eat", anyway (click here to see the brands | the scientists say it's not the same order as in Table 1):

Impressive as they may be, there is little doubt that the increases in HDL, flow-mediated dilitation (FMD), insulin sensitivity, and beta cell function, and the corresponding decreases in total cholesterol, LDL, blood pressure & co (see Table 1) will not occur in the average press release reader who picks up the next best super-size pack of chocolate at the supermarket after reading how healthy chocolate eventually is for him / her.

Against that background it's even more important to raise the awareness of often-voiced, but rarely published concerns and reservations respectable scientists have advanced with respect to the constant pimping of chocolate as a health food. Six of them have been aptly compiled by F. Willford Germino in a 2013 comment on the previously referenced article by Minor & Minor (2013):

- Publication bias. Positive results of studies get published while negative results are relegated to the back of the file cabinet, never to see the light of day or word in print. This is particularly an issue with studies that may be investigator-generated and not registered.

- Limited enrollment. Generally, only small numbers of patients were included in the study populations, with enrollees usually numbering in the low double digits. The largest study included in this review comprised only 152 patients, perhaps enough to suggest some statistical benefit, but insufficient to convince most.

- Short duration. The studies are typically short-term, lasting hours to days, with the longest study period lasting 18 weeks. Recommendations regarding long-term therapy require longer-term studies to demonstrate that efficacy continues with extended usage.

- Soft endpoints. The studies often incorporated surrogate soft endpoints (effects on nitric oxide, flow-mediated dilation, and platelet aggregation), with the assumptions that there may be a correlation with hard cardiovascular endpoints. These studies, although provocative, have often failed to demonstrate universal clinical correlation. Even modest BP reductions, when found and reported, have been seen in only a small number of patients for short periods. Additionally, the only metric used to determine BP were readings performed in the office.

- Double-blind issues. Challenges exist in the investigation of chocolate to achieve a true double-blind test. Chocolates have various tastes, colorations, and textures and any attempt to investigate the properties of one vs another must control for this. The value of single-blind studies needs to be proven.

- Translation. Flavanols are the putative active compound in chocolate that results in possible health benefit, but chocolate formulations are more varied than coffee. Broadly speaking, dark chocolates, bitter and less creamy and smooth, are of far greater benefit that the more pleasing to the American palate milk chocolate. Yet, patients will often attribute possible benefit of one to the other. Additionally, there is little in the way of standardization among chocolates to know the actual content of active compound in each sold product.

Well, if only they knew that you can already buy "brussel-sprout chocolate" ... ok, agreed, I doubt it will offer the allure of pure chocolate, the satisfaction as the melting of the fats and cocoa on the tongue release the full flavor upon the taste buds and send a message of satisfaction to the brain... and then: the blatant taste of brussel sprouts? *shocker*"Chocolate is often associated with special occasions, holidays, and festivities. It is often displayed in boxes, wrapped, and meant to be something special, and, as such, evoke warm feelings in many, harkening back to earlier, happy times as a comfort food.

Already available brussel sprout chocolate.

Certainly this bears little resemblance to the 'charms' of Brussels sprouts." (Minor. 2013)

So, it it really any wonder that press releases with titles such as "Why dark chocolate is good for your heart", "Key chocolate ingredients could help prevent obesity", "Chocolate may help keep brain healthy", or "Regular chocolate eaters are thinner, evidence suggests" drives people to hope that chocolate may provide health benefits far beyond the satisfaction we derive with its consumption. A satisfaction neither brussel sprouts, nor real cacao have to offer.

|

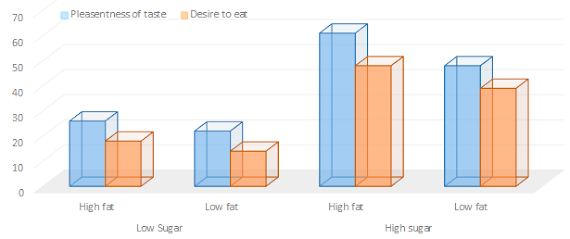

| Figure 2: Mean scores (mm) on visual analogue scale for hedonic and other perceptual responses to chocolate puddings varying in sugar and fat content; 100 = extremely pleasant (Geiselmann. 1998) |

Eating Frequency, not amount, is what counts! Well, that's at least what a recent study from the University of California, San Diego, would suggest. Unlike the frequency of chocolate consumption, which is inversely associated with BMI, "the amount of chocolate eaten was not related to BMI, favorably or adversely (eg, per medium chocolate serving or 1 oz [28 g], =0.00057 [P=.97] in an age- and sexadjusted model" (Golomb. 2012).

Beware of the being lied to: If you look closer, there is absolutely zero reliable evidence that eating more of the brown stuff, of which most people assume it was chocolote, entails any health benefits. It has become an unfortunate practice among press-release writers and even reviewers to overlook the experimental design (regular chocolate or other sweets vs. extremely high polyphenol chocolate) to make sure their pamphlet sends the previously cited message, we all want to hear: "Doing what you love to do, in this case eating chocolate is not bad for you."As the previous elaborations should have made clear, though, this statement lacks an asterisk and a dagger, to inform readers that (*) this statement is only valid if you are eating high polyphenol (="real") chocolate instead of other sweet, and that (†) even if it's "real" chocolate it will make you fat and sick, when it's eaten in excess. In moderation, on the other hand, chocolate can but certainly doesn't have to be a part of everyone's diet from Biggest Loser to Olympian athlete.

- Chobanian, Aram V., et al. "The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report." Jama 289.19 (2003): 2560-2571.

- Farhat, Grace, et al. "Dark chocolate low in polyphenols increases BMI in normal weight and overweight adults (121.3)." The FASEB Journal 28.1 Supplement (2014): 121-3.

- Ford, Earl S., David F. Williamson, and Simin Liu. "Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults." American journal of epidemiology 146.3 (1997): 214-222.

- Geiselman, Paula J., et al. "Perception of sweetness intensity determines women's hedonic and other perceptual responsiveness to chocolate food." Appetite 31.1 (1998): 37-48.

- Germino, F. Willford. "Chocolate Is Good for Me, Right?." The Journal of Clinical Hypertension (2013).

- Golomb, Beatrice A., Sabrina Koperski, and Halbert L. White. "Association between more frequent chocolate consumption and lower body mass index." Archives of internal medicine 172.6 (2012): 519-521.

- Latham, Laura S., Zeb K. Hensen, and Deborah S. Minor. "Chocolate—Guilty Pleasure or Healthy Supplement?." The Journal of Clinical Hypertension (2013).

- Miller, Kenneth B., et al. "Survey of commercially available chocolate-and cocoa-containing products in the United States. 2. Comparison of flavan-3-ol content with nonfat cocoa solids, total polyphenols, and percent cacao." Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 57.19 (2009): 9169-9180.

- Stevens, J., et al. "Associations between weight gain and incident hypertension in a bi-ethnic cohort: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study." International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders 26.1 (2002).