|

| Always hungry? Can't lose weight? "Train more and eat more" (not less!) could be the solution. |

Foright recruited recruited eleven obese study participants from the Colorado State University community and surrounding areas to test her "exercise more, eat more, lose more (easily)" hypothesis.

The enrollment criteria included: BMI between 30-43 kg/m², age 18-55 years, weight stable over the prior 12 months, desire to lose weight, and ability to exercise as assessed by electrocardiogram (ECG), resting blood pressure and a normal incremental exercise test to exhaustion with simultaneous ECG. Exclusionary criteria included: pregnancy or breastfeeding, smoking, use of medication known to affect appetite or metabolism (including but not limited to antidepressants and statins), or prior surgery for weight loss. In short, most of the participants were what we today call "healthy obese."

"The approach used in this study was a within-subjects cross-over experimental design to test the effect of high and low flux states following weight loss on resting metabolic rate and perceptions of hunger and satiety."

The study protocol was divided into four distinct phases: (1) baseline testing phase prior to weight loss; (2) weight loss phase induced by a hypocaloric diet over the course of several months; (3) weight maintenance phase in which subjects were maintained at the reduced weight for 3 weeks; and (4) experimental phase in which measures were obtained of subjects’ resting metabolic rates, fasting and post-prandial perceived hunger and satiety, fasting and post-prandial circulating glucose, insulin, and PYY concentrations, and ad libitum food intake on the 5th day following low flux and high flux phase conditions, respectively, completed in random order with a three-day washout period in between (see Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Experimental Timeline | #Order of Low Flux and High Flux were randomly assigned (Foright. 2014). |

- resting metabolic rate (RMR) measurements on day 1-4 of the low flux phase

- caloric intake was adjusted according to RMR everyday

- subjects were fed standardized meals with a macro composition of 50/35/15 (carbohydrate/fat/protein) and an energy intake that was 1.3x the RMR

- subjects had to refrain from physical activity (>3,000 steps per day)

- at the end of day 5 the subjects completed a hunger/satiety questionnaire used to assess general feelings of hunger/satiety over the prior four days of the low flux condition

- resting metabolic rate (RMR) measurements on day 1-4 of the low flux phase

- caloric intake was adjusted according to RMR everyday

- subjects were fed standardized meals with a macro composition of 50/35/15 (carbohydrate/fat/protein) and an energy intake that was 1.7x the RMR

- subjects were given pedometers and had to achieve at least 7,500 steps per day

- subjects exercised at 60% of their VO2max to burn 500kcal

- at the end of day 5 the subjects completed a hunger/satiety questionnaire used to assess general feelings of hunger/satiety over the prior four days of the low flux condition

Note: The caloric deficit that was designed to produce a 7% weight loss over the course of the 12-16 week long weight loss phase was identical in the undulating high and low energy flux phases of the study. The results are thus not a consequence of the increase in energy intake during the high flux phase (in fact the opposite was the case in some subjects, anway). The extra calories were after all burned again during the four exercise days.

"Now what is particularly interesting about the study is that the researchers did not content themselves with measuring the acute effects of high vs. low energy fluxes. They also investigated what happened after the 12-16 week weight loss phase.To minimize the acute effects attributable to the dynamic phase of weight loss on metabolic rate and on hunger and circulating appetitive hormone concentrations, subjects were maintained at the seven percent lower body weight for a three-week period prior to the start of the low and high flux conditions. During these three weeks subjects reported to the KANC every three days to monitor weight and minimize weight fluctuations. Subjects were instructed to consume a slightly increased kcalorie intake compared to the weight loss phase to maintain weight" (Foright. 2014).Put simply, the scientists wanted to know, whether the effects of high vs. low energy flux dieting would influence a dieters ability to lose weight and maintain the newly achieved weight.

|

| Figure 2: Weight loss and energy flux where exactly as the scientists had planned (Foright. 2014) |

[...a]s designed, the energy intake for high flux (x±SD: 3,191±587 kcal/d) was significantly greater (p < 0.001) than for low flux (x±SD: 2,449±406 kcal/d) (Figure 2, right). In accord with the study design, there was no difference in macronutrient composition between the two conditions (data not shown)" (Foright. 2014).Now all that would be pointless if both groups lost weight similarly effortlessly. In reality, though, On the subjects were significantly more hungry and felt less satiated at the end of each of the days during low flux.

|

| Figure 3: As you see, the mean difference was already huge. It was more than huge in in the subject who saw the greatest benefit (Foright. 2014). |

And Goran et al. (1994) found that "RMR can be elevated during a state of energy balance when energy flux is increased," and that the "magnitude of adaptive change in RMR is similar in response to increased EI [energy intake] and/or PA [physical activity]."

So what about the health markers?

The fasting insulin decreased following weight loss and was significantly lower on the LF (8.3±1.1 µU/ml) and HF (6.4±0.8 µU/ml) experimental days compared to the pre-weight loss baseline (11.8±0.6 µU/ml). In other words, while both groups saw significant increases in insulin sensitivity due to dieting, the effects were (unsurprisingly) significantly more pronounced during the high energy flux (=exercise phase).

In contrast to what the significant differences in hunger ratings would suggest, there were no general differences in fasting PYY (the satiety hormone) concentrations among pre-weight loss, low and high flux conditions respectively.

|

| Figure 5: Insulin and PYY levels of the subjects in the high and low flux phases over the course of the day (2014). |

|

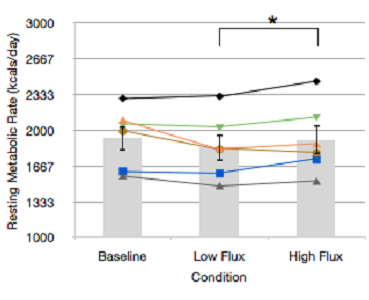

| Figure 6: Average resting metabolic rate at baseline and across 5 days of low and high flux (Foright. 2014) |

The slightly, but significantly higher resting metabolic rate during the high flux phases further underlines that there is a benefit of eating more and training more and the absence of corresponding evidence from any of the hormonal markers measured may simply be related to a "bad" choice of markers. If the researchers had determined the level of the hunger hormone ghrelin, instes, it may well have been that we would have had a physiological explanation for the "hunger difference".

The way it is, we still have the decreased subjective hunger, increased subjective satiety and increased RMR which speak in favor of the high flux state dieting. What we do not know, though, is whether the effects will be the same in athletic (vs. sedentary) subjects [based on my personal experience we will!] and whether they can be maintained for say 4 weeks instead of four days | Comment on Facebook!

- Bell, Christopher, et al. "High energy flux mediates the tonically augmented β-adrenergic support of resting metabolic rate in habitually exercising older adults." The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 89.7 (2004): 3573-3578.

- Bullough, Richard C., et al. "Interaction of acute changes in exercise energy expenditure and energy intake on resting metabolic rate." The American journal of clinical nutrition 61.3 (1995): 473-481.

- Foright, Rebecca. A high energy flux state attenuates the weight loss-induced energy gap by acutely decreasing hunger and increasing satiety and resting metabolic rate. Diss. Colorado State University, 2014.

- Goran, Miachel I., et al. "Effects of increased energy intake and/or physical activity on energy expenditure in young healthy men." Journal of Applied Physiology 77.1 (1994): 366-372.

- Rarick, Kevin R., et al. "Energy flux, more so than energy balance, protein intake, or fitness level, influences insulin-like growth factor-I system responses during 7 days of increased physical activity." Journal of Applied Physiology 103.5 (2007): 1613-1621.