![]() |

| This is what science looks like... Well, at least in the Hiscock study, where the subjects, 10 young men with at leas 12 months of training experience did regular and hammer dumbbell curls on the preacher bench - (photo | Hiscock. 2015). |

In today's

SuppVersity feature article, I am going to address not one, but two potentially highly relevant articles from the

Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Looney. 2015) and the

European Journal of Sport Science (Hiscock. 2015). What makes these papers interesting is the fact that both investigated the effect of commonly prescribed remedies to "bust a plateau" by providing novel growth triggers: (a) Training to failure and (b) modifying rep schemes and whether you fail or don't fail on every set.

If you believe in what you can read in many articles on strength training, both, training to failure and decreasing rest times / drop sets should significantly increase the muscle activity and thus - this is the most important thing - the number of motor units that are recruited during the exercises.

Want to become stronger, bigger, faster and leaner? Periodize appropriately! ![]()

30% More on the Big Three: Squat, DL, BP!

![]()

Block Periodization Done Right

![]()

Linear vs. Undulating Periodizationt

![]()

12% Body Fat in 12 Weeks W/ Periodizatoin

![]()

Detraining + Periodization - How to?

![]()

Tapering 101 - Learn How It's Done!

But is this actually true? I mean, is there a link between EMG activity, the number of motor units that are firing and the way you train? I guess, it would be wise to take a brief look at the pertinent research before we get to design and results of the individual studies. So, what do we have? As Looney et al. point out, motor unit activity can be measured through electromyography (EMG) which is commonly considered to reflect the neural drive to the muscle. Since the electrical impulse should be proportional to the number of motor units that are firing and in view of the fact that the latter determines the

acute force output, it should be obvious that increasing force demands result in higher EMG amplitude due to the greater recruitment of motor units and faster firing rates necessary to increase the contractile force.

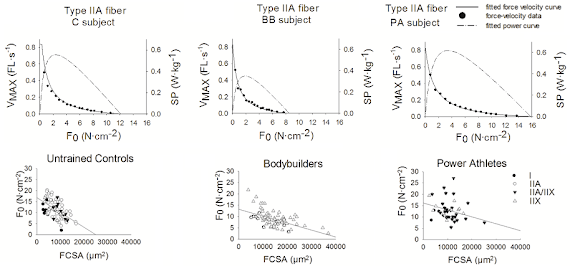

![]() |

| Figure 1: Previous studies show that the motor unit recruited (or at least it's indicator, the mean EMG values) increases over the duration of sustained or repeated muscle actions at a constant force level (Masuda. 1999 - l; Mottram. 2005 - r) |

Unfortunately, more does not necessarily help more. If you take a closer look at the existing research you have to realize you cannot stretch this proven increase of the EMG amplitude (Carpentier. 2001; Fuglevand. 1993; Lind. 1979; Masuda. 1999; Mottram. 2005; Petrofsky. 1982) infinitely. Over prolonged exercise / contraction times, the initially increasing firing rates will eventually decrease. That this is the case is interpreted by many scientists as evidence of the the fact that the initial rise in EMG amplitude is just a compensatory mechanism for sustaining contractile force as fatigue accumulates (when the individual fibers fatigue, more are recruited to sustain the same force). This hypothesis appears to be confirmed by numerous investigations that have demonstrated that EMG amplitude increases during dynamic exercise as the extent of the effort, or number of repetitions performed, increases (Hasani. 2006; Spreuwenberg. 2006; etc.).

Why is it even important that all muscle fibers contract? The reason should be obvious, but I am happy to explain it once more. It is the contraction that's responsible for the exercise induced increase in GLUT-4 receptor expression and mTOR phosphorylation. In view of the fact that the latter determine the increase in glucose uptake and protein synthesis after a workout, you obviously want as many muscle fibers to contract as possible. Or, to put it differently: If you don't use it you won't grow it, bro... well, at least not to the same / optimal extent.

This is where the "train to failure to maximize motor unit recruitment"-theory comes from. After all, this observation indicates that usually inactive motor units are going to fire only during prolonged training at high intensities (best to failure). As usual, though, there are problems with this theory:

"While the increase in EMG amplitude observed during repeated muscle actions has been explained by increased central drive necessary to sustain force as fatigue accumulates, it is inconclusive whether fatigue derived from earlier performed exercise induces greater EMG amplitude during subsequent exercise. Previous studies have shown EMG amplitude diminishes after strenuous resistance exercise protocols. In contrast, Smilios et al. demonstrated progressive increases in EMG amplitude over a series of 20-repetition sets with gradually decreasing resistance interspaced with 2-minute rest periods. Further uncertainly exists pertaining to consecutive maximal effort sets with progressively lighter resistance performed without allotted rest periods. This frequently incorporated training technique, commonly known as a “drop set”, has remained relatively uninvestigated" (Looney. 2015).

Needless to say that we all expect that lighter weights can stimulate greater motor unit recruitment, if you use them in dropsets, but as Looney et al. say, the science that would conclusively confirm that is simply not there (yet). The goals of Looney's study were thus as follows:

- Firstly, confirm / refute the assumption that EMG amplitude would be significantly greater in light resistance exercise (50% 1RM) performed in rested conditions to a maximal number of repetitions than to a submaximal number of repetitions.

- Secondly, assess whether the EMG amplitude would be significantly lower in maximal repetition sets performed in rested conditions with 50% 1RM resistance than with heavy resistance (90% 1RM).

- Thirdly, test whether the EMG amplitude would be greater in maximal repetition 50% 1RM resistance sets performed in pre-fatigued conditions (no prior rest period) than in rested conditions.

As the authors rightly point out, the "findings of this investigation would provide critical information on understanding the changes in neuromuscular physiology during dynamic exercise related to variable levels of target repetitions, resistance, and fatigue" (Looney. 2015) and may thus be of great value to scientists (initially, because the would have to still check the practical consequences of any increases in motor recruitment) and coaches + athletes (later). What the Hiscock study in which the researchers evaluated the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and its correlation with muscle activation and lactate levels can add to the table is information on the effect of another parameter: Different rest times.

![]() |

| If you don't do them as an intensity add-on / finisher don't do partial reps at all - "Full Rom, Full Gains" | more |

Don't forget that form, time under tension and the range of motion matter, as well. In 2013, for example, I discussed the results of a study by McMahon et al. that leaves little doubt that the increased mechanical stress and workload (remember work is the product of force x time) from doing exercises over the full range of motion will trigger greater morphological and architectural adaptations in response to resistance training than doing the same exercises over only a partial range of motion. Unfortunately, the evidence in favor of the significance of

optimal form (beyond going over the full range) and the

time under tension for optimal gains is less convincing and in parts contradictory.

In order to avoid any confusion, though, let's initially look at the Looney study in isolation. In said study ten resistance trained men (age, 23±3 yr; height, 187±7 cm; body mass, 91.5±6.9 kg; squat 1RM, 141±28 kg) had EMG electrodes attached to their vastus lateralis and vastus medialis muscles on two occasions:

- A drop set day, on which he subjects performed three consecutive maximal repetition sets at 90%, 70%, and 50% 1RM to failure with no rest periods in between.

- A single set day, on which the subjects performed a maximal repetition set at 50% 1RM to failure (no "dropping" involved).

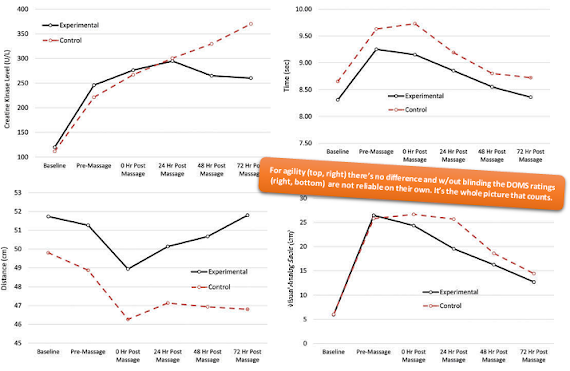

The analysis of the EMG data yielded overall unambiguous results: The maximal repetition sets to failure at 50% and 70% 1RM resulted in higher peak EMG amplitude than during submaximal repetition sets with the same resistance. In view of the fact that the peak EMG amplitude was significantly (P ≤ 0.05) greater in the maximal 90% 1RM set than on any of the other sets the subjects performed, the classic drop set with 90%, 70% and 50% 1RM should thus still have an edge over any regular "low intensity + high rep to failure" single set training. The question remains, however, whether it will also have the edge over conventional training?

![]() |

| Figure 2: Very general summary of the research interests and designs of the two studies discussed in today's SuppVersity article by Looney et al. (2015) and Hiscock et al. (2015) |

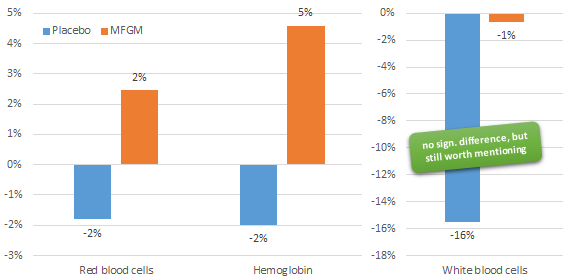

We will get back to that question in the bottom line. In the mean time, let's briefly take a look at another, quite surprising result, one that will also lead us to the results of the previously mentioned study by Hiscock et al. (2015): The lack of association between the ratings of perceived exertion (CR-10). In contrast to what most of you certainly expected, the fatigue levels did not differ over the intensity range of loads and did not reflect the degree motor unit recruitment in any way (see

Figure 3). You as an individual without the necessary technical equipment are thus probably unable to tell hor many motor units you've actually recruitment in a workout; and - even more importantly - the mere fact that you have to crawl instead of walk out of the gym is

not a sign of a productive workout.

![]() |

| Figure 4: Mean number of repetitions (left, top), rate of perceived exertion (RPE | left, bottom), and peak EMG amplitude as a measure of motor recruitment (Looney. 2015). |

You don't want to believe that? Well, bad luck for you: This result appears to be confirmed by Hiscock's study, in which 10 recreationally trained (>12 months of previous resistance training) did DB Curls and DB Hammer Curls on the preacher bench for three sets with their preferred arm at a constant load of 70% of their individual 1-RM over 4 trials:

- 3 sets × 8 repetitions × 120 s recovery between sets;

- 3 sets × 8 repetitions × 240 s recovery;

- 3 sets × maximum number of repetitions (MNR) × 120 s recovery;

- 3 sets × MNR × 240 s recovery.

After each of the exercises the participants rated their overall and active arm muscle rate of perceived exertion (RPE-O and RPE-AM) and the data was correlated with the biceps brachii and brachioradialis muscle EMG activity during each set for each trial.

![]() |

| Figure 5: Despite sign. higher volumes (see boxes) and a 100% increase in rate of perceived local muscular exertion there was no significant increase in muscle activity with lifting 70% of the 1RM for 8 vs. to failure (Hiscock. 2015). |

Just like in the Looney study, the measured rates of perceived exertion in the Hiscock study had did not correlate with with either the muscle activation or the lactate accumulation in the biceps. Rather than that, it appears as if the subjects' bicepses didn't even care about rep schemes and failure. While the RPE increased significantly, when the subjects trained to failure, the mean and peak EMG activity levels in

Figure 5 are more or less identical for all rep x intensity (+/- failure) schemes.

So what's the significance of the results, then? If you put some faith into Looney's conclusion, it is that the results of his (and I may add Hiscock's study, too) confirm "previous recommendations for the use of heavier loads during resistance training programs to stimulate the maximal development of strength and hypertrophy" (Looney. 2015).

![]() |

| SuppVersity Suggested Topical Article: "Failure, a Necessary Prerequisite for Max. Muscle Growth & Strength Gains? Another Study Says 'No Need to Fail, Bro!'" | read more |

Reducing the load and training to failure (Looney's "single set" day) or reducing the rest times and or switching from a set rep number to training to failure (Hiscock's groups A-D), on the other hand, has no effect on motor recruitment and could, in view of potentially increased recovery times due to higher rates of perceived exertion w/ training to failure, rather hinder than facilitate rapid strength and size gains. Whether the same is the case for the drop-set, though, is not 100% clear. With the peak muscle activity occurring in the first set, you cannot argue that the stimulus was weakened. On the other hand, there's a proven reduction in total volume (reps x weight | Melibeu Bentes. 2012) of which long-term studies would have to investigate whether the can impair your strength and size gains.

Overall, there is still little doubt that the results of the two studies I discussed today support the notion that "going heavy" is still the way to activate a maximal number of muscle fibers. Whether this does also mean that it is necessarily the best way to make those fibers grow and or increase their glucose uptake, however, is still not fully proven. The same goes for the usefulness of training to failure, of which some studies suggest that

failure does not matter, while others appear to indicate that "failing" is

almost necessary to maximize your gains - as usual, I've

written about both of them and will continue to do so in the future, so stay tuned if you want to be among the first to learn what works best for strength and hypertrophy training ;-) |

Comment on Facebook!

References:

- Carpentier, Alain, Jacques Duchateau, and Karl Hainaut. "Motor unit behaviour and contractile changes during fatigue in the human first dorsal interosseus." The Journal of physiology 534.3 (2001): 903-912.

- Fuglevand, A. J., et al. "Impairment of neuromuscular propagation during human fatiguing contractions at submaximal forces." The Journal of physiology 460.1 (1993): 549-572.

- Gibson, A. St Clair, E. J. Schabort, and T. D. Noakes. "Reduced neuromuscular activity and force generation during prolonged cycling." American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 281.1 (2001): R187-R196.

- Hassani, A., et al. "Agonist and antagonist muscle activation during maximal and submaximal isokinetic fatigue tests of the knee extensors." Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 16.6 (2006): 661-668.

- Hiscock, Daniel J., et al. "Muscle activation, blood lactate, and perceived exertion responses to changing resistance training programming variables." European Journal of Sport Science ahead-of-print (2015): 1-9.

- Lind, Alexander R., and Jerrold S. Petrofsky. "Amplitude of the surface electromyogram during fatiguing isometric contractions." Muscle & nerve 2.4 (1979): 257-264.

- Looney, David P., et al. "Electromyographical and Perceptual Responses to Different Resistance Intensities in a Squat Protocol: Does Performing Sets to Failure With Light Loads Recruit More Motor Units?." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research (2015).

- Masuda, Kazumi, et al. "Changes in surface EMG parameters during static and dynamic fatiguing contractions." Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 9.1 (1999): 39-46.

- McMahon, Gerard E., et al. "Impact of range of motion during ecologically valid resistance training protocols on muscle size, subcutaneous fat, and strength." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 28.1 (2014): 245-255.

- Mottram, Carol J., et al. "Motor-unit activity differs with load type during a fatiguing contraction." Journal of neurophysiology 93.3 (2005): 1381-1392.

- Petrofsky, Jerrold Scott, et al. "Evaluation of the amplitude and frequency components of the surface EMG as an index of muscle fatigue." Ergonomics 25.3 (1982): 213-223.

- Smilios, Ilias, Keijo Häkkinen, and Savvas P. Tokmakidis. "Power output and electromyographic activity during and after a moderate load muscular endurance session." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 24.8 (2010): 2122-2131.

- Spreuwenberg, Luuk PB, et al. "Influence of exercise order in a resistance-training exercise session." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 20.1 (2006): 141-144.